Namemaking, Weary Work for Whales and Men

On April Fools’ Day 2005, our plane landed in the great city of Philadelphia, safely delivering us into the hands of old friends Ned and Leslie Bustard. Ned, a publisher with Square Halo Books, had invited Andi and me to speak at their first conference: “The New Humanity: Christian Mysteries for Everyday Saints.” For more than twenty years, Ned and Leslie had been two of the most dedicated fans an artist could have, and they’d grown up to be such interesting people, full of happiness and hospitality. I wouldn’t turn them down. So there we were, driving the back roads from Philly to Lancaster, the mini-van bouncing with each wave of blacktop.

Leaving Philadelphia at our backs, I couldn’t help but think of my new favorite pianist Uri Caine, or the band The Roots, or John Coltrane for that matter — all associated with the city of Brotherly Love at one time or another. Once at the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville, I brought my teenage son Sam backstage to meet pianist Herbie Hancock and saxophonist Wayne Shorter. Locals, Bela Fleck and Jeff Coffin were also in the room to pay their respect. I reintroduced myself to Herbie, having met him briefly many years earlier at a rehearsal for Eddie Henderson’s album, Mahal. I’d been at Eddie’s home in the Berkeley Hills the week before for an audition. I remember saxophonist Prince Lasha hanging out on the redwood deck. It looked like Pharoah Sanders was with him but I was afraid to confirm. I played the Steve Swallow tune, “Hullo Bolinas” and one of my own. Eddie responded by playing me a rare Miles Davis recording. Years later I realized he’d done this to gently show me I wasn’t quite ready to fill the vacant piano spot in his band. Next Eddie guided me, and my very confused young wife to an upstairs bedroom, where he sat us down in front of the first VCR we ever laid eyes on. He pushed play on this massive machine from the future (or at least Japan) and the image and sound of the famous John Coltrane Quartet came to life (now available on DVD as The World According To John Coltrane). Eddie left us in the room alone for at least an hour. I could not believe the unmerited favor I was experiencing. I became John the Revelator caught up in a vision of jazz paradise.

I left with an address for Studio Instrument Rentals (SIR) in San Francisco and an invitation for the following week to come and hang with my musical heroes. I was twenty years old. This gave me no choice but to quit my job at Bremer’s Hardware in Yuba City so I could spend the day soaking up the funk with Herbie, Eddie, Paul Jackson, Julian Priester, Bennie Maupin, Howard King, and M’Tume. I was a horrible employee. Instead of resigning in person I sent those good people at Bremer’s a postcard of a fisherman in a little boat bringing in a gigantic catch. It said: “I got the big one.” Either my wife or mother picked up my final check for me. Men have a word for men who wimp out to this degree. Only a few years later I would record at the Automatt across the street from SIR and my mid-80s managers, the legendary Bill Graham and sidekicks Mick Brigden and Arnie Pustilnik would office just around the corner. Many years later, in Brooklyn, I recorded a song titled “Automatt” with musicians Jeff Coffin, Ben Perowsky, Hilmar Jensson, Tony Miracle, and Jaco’s son, Felix Pastorius.

When I introduced my son to Herbie, he saw that Sam was carrying a drumhead. “Whatcha got there man?”

Sam showed him the Remo head the late drummer Tony Williams had signed for him ten years earlier at a concert in Sacramento at the Crest.

“Would you sign this for me?” Sam asked.

“No man, you don’t want me to put my name on there. That’s Tony Williams.”

“I know,” Sam argued. “It’ll be even better if you and Wayne sign it, too.”

Herbie smiled wide and passed the drumhead over to Wayne.

“Check it out, man.”

“Anthony Williams,” said Wayne, nodding his head. “Anthony Williams. Anthony Williams.” And he kept on. Must have said Anthony Williams ten or twelve times in every possible inflection and pitch as if he was composing a follow-up to “Neferrtiti” — "Anthony Williams, Anthony Williams, Anthony Williams." Eventually both men signed it, but not before Wayne told some Anthony Williams stories. He especially delighted in recalling how people just didn’t understand what Tony was doing on the drum set when he first came on the scene. “Couldn’t get no respect. Just like Coltrane in Philly. Coltrane was like Jee-suss — couldn’t get NO respect in his hometown!” Philly, not his true hometown, but that’s a minor technicality really.

The Square Halo conference with Ned and Leslie was rich with good people and good stories. I was especially proud to know my wife and hear her speak such wisdom. The site of the conference was a church just up the road from Lititz, the Moravian settlement where northern California pioneer John Sutter spent his last disappointing days on earth. Sutter’s sawmill workers had left him for the Gold Rush, and he could not defend his land against the squatters who took over his land, destroyed his crops, and helped themselves to his prodigious herds. Sutter fled to Lititz where he lived out his life on the fumes of fame.

Sutter had moved to Lititz from Yuba City, California, my birthplace, my hometown, and the location of Bremer’s Hardware that I left so spinelessly for what I thought was my first step into greatness. No local Yuba City name has more history or significance than John Sutter, and the town named for him is due west, down Butte House Road ten miles or less. It’s the northern gateway to the Sutter Buttes. When I was a kid, Sutter was where the okies lived, where you fled when the Feather River spilled its banks, where country singer Rose Maddox sometimes performed, and where we buried our dead. Still do. Sutter City (as it was called for a short time) was just the tip of all things Sutter. We purchased burial plots in the Sutter Cemetery and played ball for the Sutter Buttes Little League. Most children there couldn’t explain the difference between a Jew and a Catholic, but every child knew who John Sutter was. Even then, no child left behind. Sutter was everywhere in everything.

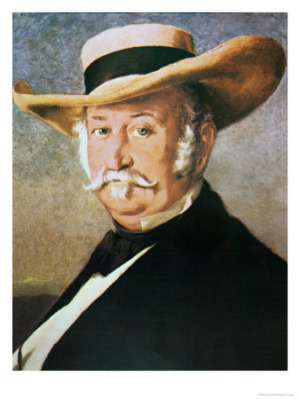

Johann Augustus Suter was born in Baden, Germany in 1803 to parents of Swiss lineage. By his early thirties life wasn’t working. Bankrupt and running from debtors, he wondered if America would do him better. Eventually it did. Like his countryman Goethe, Suter put a great deal of stock in the romantic power of self. In 1834 he left his family in his brother’s care and sailed for New York. He moved west to Missouri for a time, then the Hawaiian Islands, the Russian colony at Sitka, Alaska, and finally Mexican California in 1839. That’s when things started getting good.

Mexican California was ripe for a man with big ideas. Suter became Sutter and the land of the peaceful Native Americans was quickly transformed by agriculture, industry, and the darker ambitions of the human heart. Sutter learned everything he needed to know about the stuff of a self-interest economy: cheap labor, cheap materials, and influential friends. This is something every person in the business of making a name for himself knows. Despite Babel’s warning, history is a parade of humanity desperate to make a name for itself. Sutter’s imaginative and creative choices, as self-serving as they were, set in motion the mass population of the far west, shaping the territory into a jewel in the crown of the United States of America. So Sutter made a name for himself. One that people today, especially in California, are happy to co-opt for their own name-making purposes from the promotion of wine to healthcare.

When someone’s name is that pervasive you’ve got to ask, “Why?” What makes some personal fame timeless? What kind of spirit embeds itself in words and names to give them oomph? I’ve come to believe famous people come in two varieties: famous for all the right reasons like Jesus and Johnny Cash, and famous for all the wrong reasons like Joe the Plumber and John Sutter.

The story goes that one year after arriving in California, John Sutter became a naturalized Mexican citizen. That qualified him for a land grant, which he obtained the following year. The Governor granted Sutter 48,000 acres of land to the north and east of Yerba Buena (later to be named San Francisco). But Sutter got more than land; he received power, too. The Governor authorized Sutter to function as judge and jury, and by all means “to prevent the robberies committed by adventurers from the United States, to stop the invasion of savage Indians and the hunting and trapping by companies from the Columbia.” How Sutter came about such authority so quickly can only be explained by a very old method of making life work: pure deceit. At one time or another, most of us feel compelled to be someone or something other than who or what we are. I know this temptation well. It’s easy to think that being me is not good enough. I have to be me +. Sutter was no exception.

It is a strange by-product of life that a lie often feels safer, more reliable than the truth. I’ve known many people who would rather believe the lie they know than the truth they’ve just met. Somewhere along the way Sutter, the bankrupt adventurer, imagined for himself a military career, that of a Captain of the Swiss Guards of Charles X of France. He made it all up. Sutter parlayed this self-appointed, imaginary military title into several impressive letters of recommendation that he used to establish credit and enlist support. He was nothing if not industrious.

In order to truly change the world, history shows you’ve got to have a fort. My childhood in Sutter County was filled with the construction of all manner of forts. It seemed as if we built forts in order to learn to build a life. So too for Sutter, who built his fort at a prime location where the Sacramento River received the downhill west-flowing waters of what Sutter named the American River. He built a thick-walled adobe fort with the sweat of Hawaiian, Kanakas, and Native American labor. Sutter named his settlement New Helvetia (New Switzerland), but it didn’t stick. As with the river, the emerging city was eventually named Sacramento after the most holy sacrament, the Eucharist (or “thank you meal”). It’s an irrevocable irony that a city named after the Christ-memory and the promise of freedom and forgiveness for every race was, in fact, built on the backs of the enslaved and underpaid. I think this is why the philosopher Cornelius Plantinga Jr. described sin as something/anything “not the way it’s supposed to be.”

The Sacramento River is long (447 miles) and flows south from upstate near Mt. Shasta in the Cascades. The river acts like a person who has lived long enough to know when to keep her mouth shut. No great, world-changing utterances, just a steady flow of who and what she’s meant to be. The Sacramento can be brooding but never menacing. That is, unless you dive to the bottom and sup with the giants — white sturgeon capable of living well over a hundred years, growing 8-12 feet and a thousand pounds or more.

I’ve spent many a fishing hour out on the Sacramento with my dad, and one of two uncles, either Uncle Ron the Barber or Uncle Walt the Engineer. We were normally on the hunt for stripers or salmon, but when sardines are the bait you can hook a sturgeon now and again too. Uncle Ron the Barber would douse his hands with Vitalis before tying the sardine on his hook. He said it kept suspicious fish from detecting human scent. Uncle Ron the Barber was ahead of his time. Vitalis, normally used for healthy handsome hair, repurposed for grander achievements. Genius.

If you really want a sturgeon you should go sturgeon fishing. Which means being prepared to actually catch one. Most fishermen aren’t; we certainly never were. You know you’ve hooked a big sturgeon when it peels the line off your reel. If the line doesn’t break, which it usually does, then you let the prehistoric monster pull you up and down the river for about an hour. I say an hour because most people can hold a dream in their hearts for at least an hour. Usually after an hour, with no sign of the fish ever rising from the bottom, and woefully unable to lift the monster with your rod even the tiniest bit, you lose your dream to a consigned realism. The hopeful thought of landing the largest fresh water fish in North America becomes, “I don’t know, man, why don’t we just cut the line?” Every bone and muscle aches and you’re sweating like a stuck pig, but it’s not all loss. You’ve got yourself a good story, and stories are good medicine anytime.

My dad, Uncle Walt the Engineer, and I were fishing for stripers out on the Sacramento when we heard an awful wailing. At a distance, echoing down the river it sounded like a woman or child in horrible pain. We pulled up anchor and headed toward the sound. Soon we could see the cry for help wasn’t human at all. In a flash I understood the colloquialism “sweatin’ like a stuck pig.” Hopelessly tangled in the Himalayan blackberry vines covering the river bank was, in fact, a stuck pig and, given the 90 degree heat, likely one sweating.

With the full faculties of my twelve-year-old mind, I pondered that pig awhile. My grandparents or great-grandparents never bothered with pigs that I knew of. There were chickens, turkeys, and goats for me to know and to develop opinions and reflections on, but no pigs. Still, you pick up things along the way, bump into pig knowledge. For example, a pig’s penis is shaped like a corkscrew, and it’s physically impossible for a pig to look up into the sky.

If a pig could fly high over Northern California and follow the Sacramento River from Shasta to the San Francisco Bay, a pig would see the river make a little jog west around the Sutter Buttes. It’s that stretch of river, out past the town of Meridian, that I know best. Further downstream, on the west bank of the river about 45 minutes south of Sacramento, is Rio Vista, the home of the Rio Vista Bass Derby and Festival.

In 1985 a 40-foot, 80,000 pound whale named Humphrey swam under the Golden Gate bridge into the bay, up the Sacramento River past the Rio Vista Bridge, to Shag Slough west of Sutter Island. Nearly beached in the shallow slough 69 miles from the Pacific Ocean, Humphrey the Whale became the most famous humpback in the history of the species. “It's a federal whale,” said a government official overseeing the historical rescue. The Feds spent some money and hired an expert: Bernie Krause, musician and former member of the folk group The Weavers, finally got Humphrey turned around. To entice him back to open waters, Krause, a bioacoustician, played recordings of the feeding sounds of Humphrey’s kin. Prior to working with Humphrey, Krause’s credits included Country Joe and the Fish, George Harrison of The Beatles, The Monkees, and Jane Goodall, naturally. I once consulted Bernie for a gig I was doing with Paul Blaise and the Art Directors and Artists Club in Sacramento.

People lined the banks of the Sacramento River for miles to cheer on the homeward-bound Humphrey. He had turned around and was returning to open water. We followed the action on TV from the comfort of our living room. At the Nantucket Fish Co., a restaurant in Crockett near the Benicia bridge, whale watchers waited patiently for Humphrey’s appearance. When the wayward whale came into view, restaurant help and customers gathered on the pier outside. They cheered and partied and felt lighter in the world for having paused to care and delight in something other than themselves. I like to imagine that the better side of the “Sutterness” of all things was present in that moment, perhaps a handful of the celebrants were toasting Humphrey with a glass of Sutter Home Chardonnay or Merlot.

How do you explain such a skip in the universal flow of things? Whale-ologists suggested a sickness, perhaps parasites on the brain or an inner ear infection. The fact is, whale or man, eventually every thing makes clear that it is not the way it is supposed to be. Yet somehow, lost mammals large and small are shown cosmic favor to turn and return. As the imminent theologian J.I. Packer once explained rhetorically to Andi and me, “It’s all of Grace then isn’t it?”