A Walking Contradiction, Part Two

I have a friend who wryly describes herself as a bad Buddhist. This makes me smile. I think of Dustin Hoffman’s character in the film Little Big Man and the many vocations he pursued over a lifetime: Caucasian Cherokee, drunk, gunslinger, muleskinner, liar, and more. With each one he describes his performance as horribly lacking. Can you hear the actor’s voice? I was a horrible drunk. I was a horrible liar. Well, I was a horrible Zen Buddhist. I even received an “F” in Zen Buddhism at Cal State Sacramento — though less for aptitude and more for lack of attendance, basically a failure to drop the class after taking on a full-time music gig. Not only was I a horrible Zen Buddhist, but I learned that I could be a truly horrible person too — and now I’m not smiling.

I’ve heard it said that sin is the only major doctrine of Christianity that can be empirically proven. I agree in part, but disagree with it being the only major doctrine that can be proven. I think human beings are inescapably related to God, and that the doctrine of the image of God in humankind can be proven as well. These two major doctrines, one about the shame and the other about the glory, explain the walking contradiction that is me. I am capable of world-changing good and devastatingly bad behavior — behavior that changes your world and mine down to the most personal of relationships and enterprise. This is what I came to believe when I had no intention of believing it. Christian theologians like it when people say stuff like this. They have names for this kind of sneaky belief: prevenient grace and common grace.

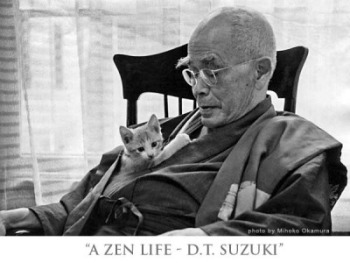

In addition to my Zen hero Gary Snyder, I read Alan Watts, Thomas Merton, and the greatest interpreter of Zen to the West, D.T. Suzuki. The editor of D.T. Suzuki’s Essays in Zen Buddhism described Suzuki as “a man who seeks for the intellectual symbols wherewith to describe a state of awareness which lies indeed beyond the intellect.” As a young aspiring Zen Buddhist, this concept always hung me up, kept me from fully entering in. I was just acquiring an intellect, let alone one robust enough to know where the intellect ended and the event horizon of new awareness began. Now with the passing of time, I like to think I understand something of Suzuki’s bent and desire.

Thanks to friends Steve Garber and Esther Meek, I have a very elementary understanding of epistemology, specifically the pioneering work on this subject from scientist Michael Polanyi. I know the impulse to “seek the intellectual symbols” to describe knowledge that operates at the tacit rather than cognitive level — most artists do. So does Michael Polanyi. Maybe the East and West poles of Suzuki and Polanyi aren’t as far apart as some might assume. Maybe both intellectuals were trying to get at something “beyond the intellect” — something more than a little elusive, something that dwells where many words or the scientific process seldom gain traction. Even when wordsmiths and scientists do sneak in and have a look around the great beyond they tend to over complicate things. Too much talking, over analysis, and second-guessing can kill insight and enlightenment on arrival.

Some of us who follow Jesus think this place of knowing (beyond or encircling the intellect) might be what we call faith, even hope and love — all perfectly legitimate ways of knowing. We also think you can hold to this belief without denigrating the intellect. Unfortunately, there’s always some school of thought trying to disengage the intellect from the authentic spiritual life. Even Christians, maybe especially Christians, have an anti-intellectual bias. This is especially ironic coming from a people who profess to know something of the mind of Christ. Where I stand, the best approach to knowing is holistic — using every good and powerful way of knowing, active and tacit, in different measure at different times all fueled by love.

You can have a real desire to find symbols that describe ways of knowing more than you can tell — at least more than you can tell by using the traditional means of description, argument, or logic. Poetry, art, and music do this symbolic work very well. Especially when they are allowed to speak their own language. It’s sad when art is not allowed to simply be. People grow dependent on the artist’s apologetic or the critic’s opinion and the human ability to know atrophies. Instead of knowing more than they can tell, they tell more than they know. Lips are moving, but all we hear is what they’ve read online or seen on TV. Not wholly inadequate sources, but life is made of more than screen-time.

To help people know in fresh ways, Jesus used the spring-loaded power of the parable. Was he trying to communicate with people on a para-cognitive level? Jump-start their hearts? All of this wondering reminds me of how people are always saying something is very Zen or Zen-like. I used to say this all the time. Everyone in our tribe did. “That’s so Zen.” No one ever asks, “Why is it so Zen?” We’re all afraid to reveal our unenlightened state.

Maybe Western Zen-talk is just convenient shorthand for “I know something is real; I’m aware of it, but it’s true that either I cannot describe it, or attempting to would be a colossal waste of time and energy. Worse yet, it would take all the fun out of it.” To borrow from a common Polanyi illustration, think of trying to explain in exhaustive detail how you know how to ride a bike. I did a little of this one day in the writing of a poem titled “Bicycle Poem No. 1.” If you’re good at analysis, you might come up with a few fun and clever descriptions of how basic bike-riding gets done. Bottom-line though? You probably know more about bike-riding than you can tell.

Do you have to know the physics of cycling in order to ride? No. Yet your thinking and behavior while riding a bike might give a spectator the impression that you are working out thousands of complicated problems in your head regarding motion, balance, and speed. The truth is, you’ve gained substantive knowledge of bike-riding over time, and this knowledge is more complex and nuanced than you have skill to describe. In short, you just know, right? Or, in Polanyi-ese, you know more than you can tell.

I didn’t know that coming to belief about the reality of sin would set me on a path of knowing that continues today. Not only was more revealed, as my alcoholic/druggie friends said it would be, but more and more is continually revealed. The enlightenment I sought through Zen has come true in the unexpected form of following Jesus in the way of love. Who knew? I didn’t.

As much as I liked Zen, it wasn’t what I needed and it didn’t answer the sin problem effectively, or provide what I thought was a fully integrated "God, People, and Earth solution." More than anything, I really wanted religious pluralism and syncretism to be my god. It’s a fit for my personality. I just want everyone to be happy and get along. I understand John Coltrane’s search and his struggle. I couldn’t stay there though. For me, I sorted it out this way. If I could create a god from a mix of gods or religions based on cherry-picking only the aspects I resonated with, then that composite god would never be greater than my own presuppositions, aspirations, prejudices, conscience, and imagination.

As it turned out, transcendence as I understood it was not what I needed anyway. I needed real-time, earthbound rescue. I needed forgiving, reconciling, restorative love.

When I started hanging out with the drunks and addicts they told me I’d never get or stay sober without a higher power. I trusted their experience. One cranky old man said his higher power was an ashtray. He said an ashtray is as good as anything. Frankly, I thought he was full of it. I chose the God of the Bible.

There was a particularly dark hour in my past, when after having betrayed my father for the last time, he told me to pack my things and be gone by the morning. After all the misspent words had been spoken, after all the tears and false promises ceased, he came into the guest bedroom where I’d gone to sulk. There was no fight left in him. He laid a Bible on the bed. “Son,” he said, “everything that you’re looking for is in this book.” Then he turned and left the room.

I won’t even print my response. It’s too shameful to write.

And so, many months later, having been a spiritual tourist for my whole life, I somehow landed on the God of the Bible as my higher power. My memory of the rationalization is a little fuzzy. But it seems to me the choice was about giving God another shot at me, another go-round. Lucky him.

In time I admitted I was powerless over drugs and alcohol, especially alcohol. In the light of a little sobriety, it was humiliatingly obvious that my life was unmanageable. On faith, and the advice of a bunch of other losers, I came to believe that a Power greater than myself could restore me to sanity. And of course, I made a decision to turn my will and life over to the care of the God of the Bible.

In my mind I was visualizing the Bible as being the Protestant version with all the achingly human Jewish stories and poetry on the front end and the Jesus story at the back. I had always liked Jesus but had rejected the organized religion of Christianity as a part of my overall distrust of institutions and authority.

I prayed to the God of the Bible in the morning and at night. “God of the Bible, please help me stay sober today.” Later in bed, “God of the Bible, thank you for helping me stay sober today.” That simple. No flourishes. No thees, no thous. Just, help. And, thanks.

What could it hurt?

I continued to work the Twelve Steps, admitting the exact nature of my wrongs. All of this went into the notebook and led to my belief in the reality of sin. I prayed my morning and evening prayers and began to elaborate a bit – asking the God of the Bible to change my character, my whole way of being. I even began to pray for family provision, for help in my marriage and the whole of life. My prayers were about what was happening under our roof. I figured I’d get to other matters of global and mutual concern once it was clear I’d live to see twenty-seven.

A year went by and I got a call from a saxophonist named Mike Butera. Mike and I did a few gigs together at the top of the Holiday Inn in downtown Sacramento. I knew he was a Christian. At least that’s what people said as they bemoaned what a waste it was for a talented person like Mike to become such a thing. Mike was an old friend of David Kahne, the producer I worked with in San Francisco on my first demos for A&M Records. In our neighborhood, Mike was a giant of a musician.

I suppose we mocked Christians, particularly the new variety of born-again types, because we thought we knew what becoming a Christian actually meant. Generally speaking, we thought it involved a lot of rule-following. That it involved giving up a number of things you enjoyed, to do a number of things you had no idea whether you’d enjoy or not. There was also a sense that Christians were given to moralizing, an attitude of superiority, hypocritical behavior, and were judgmental of others.

As a means of connecting on common ground with Mike I told him I’d been praying for work and was grateful for the gigs. Later he asked me whom I prayed to. I told him the God of the Bible. I figured he’d be pleased — one point for the home team and all that.

I went up to Lake Tahoe for a couple of weeks to play with a country band in the small room at Harrah’s. When I returned Mike called me. The conversation went something like this.

“You know I’m a Christian, right?”

“Yea.”

“Well I’ve been praying for you ever since we played together. And every time I pray for you I sense that God wants me to ask you something. But I’ve been too afraid to just call you up and ask you. But this sense of what I’m supposed to do is so strong I just can’t avoid it anymore.”

“OK.”

“So, would it be alright if I came over and prayed with you?”

I told him sure, come on over. It did seem a little awkward, but my heart was open. I was just glad to be alive and have a future. If it would make Mike Butera happy to pray with me, it was the least I could do for him. He’d taken a chance on a guy with a very bad reputation and given him work. I figured, I pray in the morning; I pray at night; I can pray in the middle of the afternoon, too.

Mike arrived shortly after our phone conversation. He had a few thoughts and questions to offer before we prayed. He was trying to tell me I couldn’t get to God on my own terms and I especially couldn’t work my way to God by my own good works. No problem there. I hadn’t had any in awhile. He said it was like trying to swim to Hawaii from California. I think he wanted me to know that I couldn’t save myself — a fact already glaringly true. I knew I couldn’t swim to Hawaii metaphorically or otherwise. Jesus, he said, is the bridge over the ocean of impossibility, doing for people what they can’t do for themselves. Quoting the Bible, Mike said that Jesus came into the world to save sinners — that he was God’s Son and had the power to forgive sin. I’d heard that before. Then he started making me uncomfortable.

He told me that Jesus is the only way to God and that salvation is found in no one else and no other thing. That’s why all those bumper stickers said "One Way and Jesus Saves." More disturbing and confusing were Jesus’ own words (what I knew as the red words in the Bible). The words that really gave me pause were: “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to God the Father except through me.”

Then the questions began and two eclipsed all others. Mike asked me if I thought I needed a savior. I might have laughed out loud. If anyone needed to be saved from his self-absorbed ways, from his circumstances, from a parade of poor choices and failures, from what I’d come to believe was sin, I did. Yes, I needed a savior, practically and cosmically.

Next he asked, “Do you think Jesus could be that savior?”

Then I knew. I knew more than I could tell. I was experiencing a kind of awareness I had no prior experience with or words to describe. There was line drawn in my heart and the whole of the universe. And if I crossed over that line, admitting out loud that yes, I think Jesus is the savior I need, there’d be no turning back. This was real and it was happening and I couldn’t stop it. Faith had snuck up on me. I was scared and flushed with heat. Now that I knew, I couldn’t act as if I didn’t. I was flummoxed. I didn’t know what to do. I felt like I was dangling over the earth from outer space. How could I be sure? What if I was wrong?

Then, fully aware, I stepped across the line.

Not everyone does, but I had a very physical reaction. I was overcome with gratitude and I wept uncontrollably. God had heard my cries for help bouncing off his satellites and he sent a saxophonist to offer rescue, forgiveness of sin, and a new life. In a fraction of a second I knew love more completely, more extravagantly than I’d ever known it. In short, I was shown mercy.

Finally, we prayed. Not a typical afternoon for two musicians accustomed to going to work at 10:00 pm.

My life changed that day and I’ve never turned back from following Jesus in the way of love. For me, love is the most powerful way of knowing and being known. I can say with all confidence that the love of God in Christ Jesus is authentic and trustworthy. I would add that having an interest in what Jesus is interested in is a true and better way to live.

Holding on to this conviction has never been easy though. At every turn there is someone coming in the name of Jesus misrepresenting his interests, including this writer/musician. It can make you wish you had no affiliation with anyone who uses his name, especially those who speak and behave as if they have him on speed dial. Jesus must be the most co-opted character in history. Everyone wants a piece of him. People distort his mission in service of their own. Some are earnest, yet misinformed and misled. Others are downright evil and psychopathic. Some are the snake-oil salesman of our time. But many, many more who come in his name are good and trustworthy — flawed, broken, and in process like everyone else, but beautiful still, and truly in his tribe.

I was in the green room, backstage at a U2 concert several years ago. I stood around a table with friends and listened as a famous journalist told a story. The writer had published a very favorable op-ed piece in The New York Times about a Christian — a well-known British theologian. Not a common occurrence at all. It wasn’t long before the writer received a phone call from a native New Yorker, perhaps one of NYC's and the world’s most famous musicians — someone not a Christian. The story goes that the musician wanted to know if the writer was for real. Did he really think that any Christian could be taken seriously? Wasn’t the very idea of allowing for such a thing antithetical to reason, to pluralism, to the progress of society? And so on.

The journalist, himself not a Christian, set up a meeting between the Englishman and the New Yorker. They met and the New Yorker was given time to rant about why Christians can’t be taken seriously. For example: their unholy alliances, incessant meddling, exclusive truth claims, far-right politics, homophobia, lack of sophistication, warmongering, and just plain stupidity. After awhile the Brit acknowledged the occurrence of all of it and said something to the effect of, “What about Jesus? Let’s turn our attention to him.”

Jesus asked his disciples, “Who do people say I am?” This is the kind of question that reproduces questions. People say many things about who Jesus is. But who do I say he is? What did Jesus say about himself? What can be known about his mission? What are his followers supposed to concern themselves with? Am I living congruent with this mission on earth? And so the questions go.

It is easy to become distracted by all the incongruent and contradictory stories people who claim association with Jesus are telling through their confused and broken lives. Awareness of the wreckage is important. You want to take care in choosing the people you team up with and give your allegiance to. But don’t stare too long at the mess. Look to Jesus and carry on. Whenever the wreckage distracts me I’ve learned to turn my attention to a sobering question: What kind of story am I telling through the life I’ve been given?

It is also easy to overlook or forget that the life of following Jesus is extended to all people regardless of the quality of their performance as human beings. A merciful, life-changing truth I am so very grateful for. Jesus’ gift to the world is rescue, forgiveness, love, and purpose. I’ve yet to meet anyone that doesn’t need a little of these, or in my case, a lot.

I no longer seek only intellectual symbols to describe the sudden state of awareness I experienced the day I started following in the way of Jesus. I'm equally committed to a faithful, sustainable embodiment of that unique awareness in day to day life. In all ways, at all times, everywhere and in everything, the love of God, people, and planet is my work and pleasure.