So rather than read further, which would’ve been much easier, I decided to take the ballpoint pen and lined notebook paper and draw what was right before me — and do it quickly, without proper paper or the need to prettify my work. I did opt for color because the green was so lush and bright with the afternoon sunlight shining through the leaves, so I found a couple of green markers and sat there in the sun happily coloring away, like I often did as a child. Did I capture the head of Romaine perfectly? Not at all. But did I begin to glimpse its infinite beauty, the curtain of one leaf folded inside another, the veins like tiny circuitry? I did, indeed.

All in Visual Art

We wanted to respond by making, not just critiquing or even experiencing. In fact, we spent our four-hour drive home that evening discussing work and beginning to outline several collaborative projects. We were intellectually and emotionally exhausted, yet enlivened for work (our various cups of coffee throughout the day helped, too). These paintings cause the viewer to take a life-giving, culture-making posture before she even realizes that she has begun to stand. This is the generative nature of good art/work.

We wanted to respond by making, not just critiquing or even experiencing. In fact, we spent our four-hour drive home that evening discussing work and beginning to outline several collaborative projects. We were intellectually and emotionally exhausted, yet enlivened for work (our various cups of coffee throughout the day helped, too). These paintings cause the viewer to take a life-giving, culture-making posture before she even realizes that she has begun to stand. This is the generative nature of good art/work. Despite my deep longing to be among the ranks of what I call the “true” artists, the kind who can effortlessly dress themselves in wonderfully whimsical, sophisticated clothing and decorate their homes with lovely abstract art that has deep roots in poetic allusion, I am really too poorly dressed and my home too pathetically decorated to ever count myself among their ranks.

Despite my deep longing to be among the ranks of what I call the “true” artists, the kind who can effortlessly dress themselves in wonderfully whimsical, sophisticated clothing and decorate their homes with lovely abstract art that has deep roots in poetic allusion, I am really too poorly dressed and my home too pathetically decorated to ever count myself among their ranks.Interview Series: MAKING — A Conversation with Bruce Herman

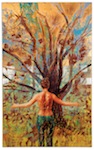

I dream of the world as sacred space — as a living cathedral. Man-made cathedrals merely echo the natural world with its soaring sequoias, canyons, oceans, mountain peaks. This world was made by a Maker who loves and enters the creation to know it from the inside. This Maker is not aggressive or possessive as we humans understand Him, but is rather hidden, loving, generous to a fault.

We listen for a moment when we might become whole / from our ruptured sense of belonging.

We listen for a moment when we might become whole / from our ruptured sense of belonging.Interview Series: MAKING — A Conversation with Kim Thomas

I absolutely think that the history of frequent moves, adjusting, new people — all that affects my making today. It takes a lot of courage to be a maker of any kind. It requires many decisions, commitments, and lonely times in your head. The nomadic life built up my courage for new things and change, sort of immunized me to sameness, and made me invite the adventure of mystery and unknown.

The mountain doesn’t look like the mountain when you’re on it. Often enough, it doesn’t look like much at all. Like standing only a few inches away from one of Georges Seurat’s pieces, all I see are points of color. It’s just dots, at least that’s true to some degree. Yet I’d venture a guess that Seurat was not primarily or initially moved by a vision of tiny marks on a canvas but that he took up the brush and diligently, meticulously made those millions of tiny marks because he was moved by a vision of sand and water or skin and eyes.

The mountain doesn’t look like the mountain when you’re on it. Often enough, it doesn’t look like much at all. Like standing only a few inches away from one of Georges Seurat’s pieces, all I see are points of color. It’s just dots, at least that’s true to some degree. Yet I’d venture a guess that Seurat was not primarily or initially moved by a vision of tiny marks on a canvas but that he took up the brush and diligently, meticulously made those millions of tiny marks because he was moved by a vision of sand and water or skin and eyes. There is never a simple answer to the question I am frequently asked: “What do you do with your time when not touring or playing music?” Perhaps the better question is, Why do you do what you do? Why cull together (more like cobble) a mishmash income year-in and year-out — each year the same, each one different, each one in hindsight a miracle? The years carry with them the same struggle, the same burden, only clothed in different hides. Some years are grimier, more pungent than others.

There is never a simple answer to the question I am frequently asked: “What do you do with your time when not touring or playing music?” Perhaps the better question is, Why do you do what you do? Why cull together (more like cobble) a mishmash income year-in and year-out — each year the same, each one different, each one in hindsight a miracle? The years carry with them the same struggle, the same burden, only clothed in different hides. Some years are grimier, more pungent than others. That word: struggle.

If, however, you are a person who needs to gear up to visit an art museum, if you feel anxious about the way these hallowed halls of priceless history and beauty leave you feeling — how should I say it? — a little dumb, read on. I’m going to tell you how to walk into an art museum like you own the place. I’m going to liberate your conscience, affirm your intelligence, give you focus, and teach you how to develop a lifelong love of not only art but of the museums that house it.

If, however, you are a person who needs to gear up to visit an art museum, if you feel anxious about the way these hallowed halls of priceless history and beauty leave you feeling — how should I say it? — a little dumb, read on. I’m going to tell you how to walk into an art museum like you own the place. I’m going to liberate your conscience, affirm your intelligence, give you focus, and teach you how to develop a lifelong love of not only art but of the museums that house it.Celebrating 20 Years of Art House America

In late October and early November 2011 we celebrated Art House America’s twentieth anniversary. With three events — two in our home, the Art House, and one at The Village Chapel near downtown Nashville — we looked back over twenty years of Art House history; enjoyed amazing music, beautiful food, and the company of people from all eras of the Art House America story. Twenty years still seems quite extraordinary when we look back on our beginnings.

Because my life is filled with ordinary moments, ordinary things are often the subjects of my photos. A table setting, the unmade bed, flowers in the garden, my little one scooting across the floor: these were the things that filled my life and comprised my days. This was the stuff my photography was made of. It was a challenge to find beauty in my daily life, but I searched continually. It multiplied my gratitude. I recorded my days and gave thanks.

Because my life is filled with ordinary moments, ordinary things are often the subjects of my photos. A table setting, the unmade bed, flowers in the garden, my little one scooting across the floor: these were the things that filled my life and comprised my days. This was the stuff my photography was made of. It was a challenge to find beauty in my daily life, but I searched continually. It multiplied my gratitude. I recorded my days and gave thanks. Reading was an escape, but not an unhealthy one. It didn’t enable me to deny my grief or the strain our family was under. It didn’t distract me from my children or make me wish for another life.

Reading was an escape, but not an unhealthy one. It didn’t enable me to deny my grief or the strain our family was under. It didn’t distract me from my children or make me wish for another life. In fact, the simple act of allowing myself the luxury of literature served to inspire my days with my children. I was a better thinker — more happy, more energized, and more full. Reading served as a wholly reparative act, something that offered renewal at a time when everything felt out of sorts.

Rembrandt was no dummy. He knew he was a great artist, no question. But he also knew he wasn’t limitless. And one of his apparent limits was his inability to satisfy what people sometimes wanted him to be. This must have been very frustrating at times. Surely there must have been days when he would’ve loved more than anything else in the world to be for another person exactly who they wanted him to be.

Rembrandt was no dummy. He knew he was a great artist, no question. But he also knew he wasn’t limitless. And one of his apparent limits was his inability to satisfy what people sometimes wanted him to be. This must have been very frustrating at times. Surely there must have been days when he would’ve loved more than anything else in the world to be for another person exactly who they wanted him to be. It inspires me to ponder the possibilities of our interactions with strangers outside of our social comfort zone. We could start by befriending and serving them, then really see our neighbors through art — perhaps by photography, recording or writing their stories, or making a short documentary film. Or we could simply talk with them, know who they are.

It inspires me to ponder the possibilities of our interactions with strangers outside of our social comfort zone. We could start by befriending and serving them, then really see our neighbors through art — perhaps by photography, recording or writing their stories, or making a short documentary film. Or we could simply talk with them, know who they are. You might not understand or connect with those images this year or next year. But we’re not in a hurry; the Spirit’s not in a hurry. And it might be another moment at another time in a different season of life that something about one of those images really begins to mean something to you. It just takes spending time with it.

You might not understand or connect with those images this year or next year. But we’re not in a hurry; the Spirit’s not in a hurry. And it might be another moment at another time in a different season of life that something about one of those images really begins to mean something to you. It just takes spending time with it. My husband, daughter, and I were in upstate New York for an extended vacation to see family, and I shot through the roll in three days. After each photograph I pulled the camera away from me to see what it looked like, a habit I’ve acquired with my DSLR, only to be reminded that this type of photography was not immediate. I had to wait. I had to take my time, adjust the camera and the focus carefully, and wait until the entire roll was exposed to take it to be developed.

My husband, daughter, and I were in upstate New York for an extended vacation to see family, and I shot through the roll in three days. After each photograph I pulled the camera away from me to see what it looked like, a habit I’ve acquired with my DSLR, only to be reminded that this type of photography was not immediate. I had to wait. I had to take my time, adjust the camera and the focus carefully, and wait until the entire roll was exposed to take it to be developed. Whenever I walk towards the austere building, I’m struck anew by the genius of its placement in a cozy neighborhood where people live, the true life of a city. The idea of sanctuary comes alive between the quiet streets. I’m soothed under the shade of old, twisting oak trees. I take refuge from the sweltering Texas sun by snagging a bench under the high, undulating awnings outside, or by opening a tall glass door to the Menil itself, flowing with cool air and natural light filtered by means of louvers, skylights, and massive windows.

Whenever I walk towards the austere building, I’m struck anew by the genius of its placement in a cozy neighborhood where people live, the true life of a city. The idea of sanctuary comes alive between the quiet streets. I’m soothed under the shade of old, twisting oak trees. I take refuge from the sweltering Texas sun by snagging a bench under the high, undulating awnings outside, or by opening a tall glass door to the Menil itself, flowing with cool air and natural light filtered by means of louvers, skylights, and massive windows.Hope in Haiti

In our little town of Nashville, the photographer Jeremy Cowart is something of a rock star. I suspect his renown is growing all around the world. When you consider that he’s made pictures of Sting, Imogen Heap, Carrie Underwood, Taylor Swift, Courtney Cox, Maggie Gyllenhaal, Ryan Seacrest, and traveled with Britney Spears in 2009 as her tour photographer, some fame and name recognition makes sense.

My favorite project that Jeremy envisioned is one called Help Portrait. Help Portrait is a world-wide movement stirring the hearts and hands of photographers to find someone in need, take their portrait, print it, and give it to them for free.