I remember which bookcase it was on, where it was on the shelf, what the light was like. Maybe I opened it to a sentence that might as well have been in neon, a passage I admired for its construction and loved for its truth. I've kept the book all these years and reread it, or at least part of it, a few times (evidenced by the geological strata of marginal notes). And for decades I’ve kept a little sign on my desk with one of her sentences, printed in a font that now seems to scream 1990s: “Work is the backbone of a properly conducted life, serving at once to give it shape and hold it up.”

All in Visual Art

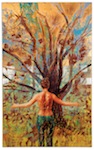

The Ongoing Search for Gratitude

I need to enumerate the good things in my life. I need to lift my camera to my face in order to see the gratitude. I need to write about it every day and share it with whoever will listen. I need to look around and pay attention. I need to say thank you to my Creator, on good days and bad.

Bright Road

The best artists don’t do all the work. They drop the bread crumbs that lead down the path of discovery. Every day, we’re given glimpses of eternity if we’ll only be willing to look beyond our circumstances and to see with eyes of faith. As C.S. Lewis wrote, “The first demand any work of art makes upon us is surrender. Look. Listen. Receive. Get yourself out of the way.”

The church was a place of incredible, deliberate, beauty. It had been some time since I’d been in a place of worship so utterly beautiful. As I walked down the main aisle and then the smaller aisles at the south and north portals, my son walked beside me. He’d never been in a church like this. It was his first time to behold, and in his little mind configure, how a church can look like this. Here is a human-made artifact of craftsmanship that, somehow, actually embodies the joy—the nearly incomprehensible reality—of Emmanuel, God with us.

The church was a place of incredible, deliberate, beauty. It had been some time since I’d been in a place of worship so utterly beautiful. As I walked down the main aisle and then the smaller aisles at the south and north portals, my son walked beside me. He’d never been in a church like this. It was his first time to behold, and in his little mind configure, how a church can look like this. Here is a human-made artifact of craftsmanship that, somehow, actually embodies the joy—the nearly incomprehensible reality—of Emmanuel, God with us.

Like committing crummy jokes to memory, remembering is intentional, the discovery of great gain in contentment. Where the debris of spilled baggage reaches its angle of repose, the place where physical objects come to rest along an incline (to borrow from Wallace Stegner), there is rest from the near-constant onslaught of shame, of striving to be enough, to make ourselves worthy, to, in effect, make gods of ourselves. And maybe not being enough is a healthy place to be, a place where God is good and is enough, all the time.

Like committing crummy jokes to memory, remembering is intentional, the discovery of great gain in contentment. Where the debris of spilled baggage reaches its angle of repose, the place where physical objects come to rest along an incline (to borrow from Wallace Stegner), there is rest from the near-constant onslaught of shame, of striving to be enough, to make ourselves worthy, to, in effect, make gods of ourselves. And maybe not being enough is a healthy place to be, a place where God is good and is enough, all the time.

I find it hard to sit with people.

I find it hard to sit with people.

I wish I meant that I find it hard to sit with people in a cramped room with a broken A/C or in a bad jury trial or even in a hospital waiting room. To my mind this is more understandable. But I mean I find it hard to sit with people in general. Like at a diner for more than half an hour. Or at a party. Or at the dinner table. Or at a park. Or on a walk. My social self, though, operates pretty adroitly, and I can spend hours at a diner or a party or a dinner table and have a pretty good time — it’s just that after awhile, something under my skin starts to crawl.

Don’t be surprised if you’re making bad art. Don’t be discouraged. And whatever you do, don’t stop. Keep making bad art. Not because you’re wrong about your self-evaluation — you might be producing some really awful stuff. But just because the thing you’re working on is a ripe mess doesn’t necessarily mean it’s time to stop working. On the contrary, that might be both the worst time and reason to quit. I think you need to make bad art in order to make anything better. I know that’s been the case for me.

Don’t be surprised if you’re making bad art. Don’t be discouraged. And whatever you do, don’t stop. Keep making bad art. Not because you’re wrong about your self-evaluation — you might be producing some really awful stuff. But just because the thing you’re working on is a ripe mess doesn’t necessarily mean it’s time to stop working. On the contrary, that might be both the worst time and reason to quit. I think you need to make bad art in order to make anything better. I know that’s been the case for me.

Sometimes it’s a shoulder or a hand combing through hair. Always it’s a simple gesture or posture that says something about the person that the whole face never could. And I love that. I love the faceless portrait.

Sometimes it’s a shoulder or a hand combing through hair. Always it’s a simple gesture or posture that says something about the person that the whole face never could. And I love that. I love the faceless portrait.

My involvement is about being the guy behind the thing that says, “Pay attention to this.”

My involvement is about being the guy behind the thing that says, “Pay attention to this.”

If I can be the person that directs others to a special thing, I’m perfectly fine and I like that anonymity. That’s my own job well done.

I have learned that on my own, in my response to the call of creation and the Creator, I am finite. I understand a few small truths and can reach only so far alone. I cannot teach myself all that I need to know and understand. When I find myself pushing the constraints of this finitude, I need the gifts of others to pull me through the fog into the next clearing. I will not reach my destination — nor even understand it — without them. I would like to. I long for independence and self-actualization. I want to do things on my own. But the fact is, I lack much.

I have learned that on my own, in my response to the call of creation and the Creator, I am finite. I understand a few small truths and can reach only so far alone. I cannot teach myself all that I need to know and understand. When I find myself pushing the constraints of this finitude, I need the gifts of others to pull me through the fog into the next clearing. I will not reach my destination — nor even understand it — without them. I would like to. I long for independence and self-actualization. I want to do things on my own. But the fact is, I lack much.

There’s an aloneness to art. We type, paint, sculpt, compose in isolation. We create to realize our theologies, philosophies, hurts, joys, doubts, faiths. We create to understand and work out our lives. And because we worship what we perceive to be the fount of truth and beauty (a God or gods, self, nature, universal energy, materials), we create to worship.

There’s an aloneness to art. We type, paint, sculpt, compose in isolation. We create to realize our theologies, philosophies, hurts, joys, doubts, faiths. We create to understand and work out our lives. And because we worship what we perceive to be the fount of truth and beauty (a God or gods, self, nature, universal energy, materials), we create to worship.

But while worship begins as a personal endeavor, it involves other people around us.

So, in order for me to think justly about my world, I have to know my world the way my Creator does — namely, that I belong to my world and it belongs to me. And I belong more immediately and vitally to my immediate surroundings. As it relates to people, justice is rooted in God’s desire for people. In my opinion, that desire is never general and statistical but always particular and personal. So if I am to live more justly and foster truth, goodness, and beauty, I must localize. I must know, personally and particularly, the place and the people to whom I’ve been given.

So, in order for me to think justly about my world, I have to know my world the way my Creator does — namely, that I belong to my world and it belongs to me. And I belong more immediately and vitally to my immediate surroundings. As it relates to people, justice is rooted in God’s desire for people. In my opinion, that desire is never general and statistical but always particular and personal. So if I am to live more justly and foster truth, goodness, and beauty, I must localize. I must know, personally and particularly, the place and the people to whom I’ve been given.The Zen of Seeing

So rather than read further, which would’ve been much easier, I decided to take the ballpoint pen and lined notebook paper and draw what was right before me — and do it quickly, without proper paper or the need to prettify my work. I did opt for color because the green was so lush and bright with the afternoon sunlight shining through the leaves, so I found a couple of green markers and sat there in the sun happily coloring away, like I often did as a child. Did I capture the head of Romaine perfectly? Not at all. But did I begin to glimpse its infinite beauty, the curtain of one leaf folded inside another, the veins like tiny circuitry? I did, indeed.

We wanted to respond by making, not just critiquing or even experiencing. In fact, we spent our four-hour drive home that evening discussing work and beginning to outline several collaborative projects. We were intellectually and emotionally exhausted, yet enlivened for work (our various cups of coffee throughout the day helped, too). These paintings cause the viewer to take a life-giving, culture-making posture before she even realizes that she has begun to stand. This is the generative nature of good art/work.

We wanted to respond by making, not just critiquing or even experiencing. In fact, we spent our four-hour drive home that evening discussing work and beginning to outline several collaborative projects. We were intellectually and emotionally exhausted, yet enlivened for work (our various cups of coffee throughout the day helped, too). These paintings cause the viewer to take a life-giving, culture-making posture before she even realizes that she has begun to stand. This is the generative nature of good art/work. Despite my deep longing to be among the ranks of what I call the “true” artists, the kind who can effortlessly dress themselves in wonderfully whimsical, sophisticated clothing and decorate their homes with lovely abstract art that has deep roots in poetic allusion, I am really too poorly dressed and my home too pathetically decorated to ever count myself among their ranks.

Despite my deep longing to be among the ranks of what I call the “true” artists, the kind who can effortlessly dress themselves in wonderfully whimsical, sophisticated clothing and decorate their homes with lovely abstract art that has deep roots in poetic allusion, I am really too poorly dressed and my home too pathetically decorated to ever count myself among their ranks.Interview Series: MAKING — A Conversation with Bruce Herman

I dream of the world as sacred space — as a living cathedral. Man-made cathedrals merely echo the natural world with its soaring sequoias, canyons, oceans, mountain peaks. This world was made by a Maker who loves and enters the creation to know it from the inside. This Maker is not aggressive or possessive as we humans understand Him, but is rather hidden, loving, generous to a fault.

We listen for a moment when we might become whole / from our ruptured sense of belonging.

We listen for a moment when we might become whole / from our ruptured sense of belonging.Interview Series: MAKING — A Conversation with Kim Thomas

I absolutely think that the history of frequent moves, adjusting, new people — all that affects my making today. It takes a lot of courage to be a maker of any kind. It requires many decisions, commitments, and lonely times in your head. The nomadic life built up my courage for new things and change, sort of immunized me to sameness, and made me invite the adventure of mystery and unknown.

The mountain doesn’t look like the mountain when you’re on it. Often enough, it doesn’t look like much at all. Like standing only a few inches away from one of Georges Seurat’s pieces, all I see are points of color. It’s just dots, at least that’s true to some degree. Yet I’d venture a guess that Seurat was not primarily or initially moved by a vision of tiny marks on a canvas but that he took up the brush and diligently, meticulously made those millions of tiny marks because he was moved by a vision of sand and water or skin and eyes.

The mountain doesn’t look like the mountain when you’re on it. Often enough, it doesn’t look like much at all. Like standing only a few inches away from one of Georges Seurat’s pieces, all I see are points of color. It’s just dots, at least that’s true to some degree. Yet I’d venture a guess that Seurat was not primarily or initially moved by a vision of tiny marks on a canvas but that he took up the brush and diligently, meticulously made those millions of tiny marks because he was moved by a vision of sand and water or skin and eyes. There is never a simple answer to the question I am frequently asked: “What do you do with your time when not touring or playing music?” Perhaps the better question is, Why do you do what you do? Why cull together (more like cobble) a mishmash income year-in and year-out — each year the same, each one different, each one in hindsight a miracle? The years carry with them the same struggle, the same burden, only clothed in different hides. Some years are grimier, more pungent than others.

There is never a simple answer to the question I am frequently asked: “What do you do with your time when not touring or playing music?” Perhaps the better question is, Why do you do what you do? Why cull together (more like cobble) a mishmash income year-in and year-out — each year the same, each one different, each one in hindsight a miracle? The years carry with them the same struggle, the same burden, only clothed in different hides. Some years are grimier, more pungent than others. That word: struggle.