It started as a flippant statement.

Brenda and I were sipping Malbecs, dodging two-year-old tackles as the men grilled out back, talking art.

We talked about the aloneness of art and our desires to share these things we’ve created, to be a part of a larger dialogue. We talked about discipline and the difficulties of creating every day and, perhaps more onerous, of sending our work out into the world to group shows and journals, to auctions and agents.

“We should do something together,” Brenda said. “A collaborative piece.”

The men returned with the salmon, and we arranged the baby in the high chair, the toddler in his seat (more or less), the food on plates. Our talk then turned to other subjects — church, work, the usual.

I didn’t know if she meant it or if it was one of those things that get lost in the laundry. But I hoped.

* * *

I wrote my first story in elementary school. Then I wrote a second, and a third. Stories about princesses and whales. Detective stories about murders on school trips. Fanciful tales set in foreign lands. I didn’t know why I loved to write, why stories and characters and words fascinated me. Mostly, I still don’t understand these things — the euphoria of seeing a plot unfold, characters transform and themes emerge, the spaces in finding the precision and patterns of words and syllables, the sleepless nights as sentences and paragraphs echo in my head. As with anything we love, I wanted to share this with others.

So I did what any elementary school girl would do. I formed a club.

We called it The Writer’s Block, oblivious of the shivers that term would later cause. We had a president, vice-president, treasurer, and secretary (for which position I conscripted my little sister). Our mission: write stories and sell them for a quarter each. Being more artists than entrepreneurs, we wrote more than we sold (not unlike my current trend), but we didn’t really gather for sales. We gathered to share our work. To partake in the joy of creating. To practice in community.

* * *

We live governed by celebrity — the nobility of our time. Despite our rages against Hollywood for causing this phenomenon, history attests that this is the way of fallen humanity. The Israelites wanted a tall and handsome king. Greek and Roman gods started wars over popularity contests. Paul wrote against the Corinthians’ obsession with status and fame in his letters to them (if the Corinthians had Internet, they would’ve obsessively checked Facebook for “Likes” and comments, Amazon for rankings, Twitter for retweets and replies as much as we do).

Art takes on the same yoke. We seek affirmation of our identities and personalities, our gifts and talents, our hard work and training (formal or informal) in public arenas: book deals, gallery shows, blogs with large followings (and the right followings), downloaded albums. Art becomes little more than self-expression and any response to our work we take as a personal response to our very identities.

As a corrective, we ask ourselves if we’re content to create in obscurity. Would I write if I knew from the beginning I’d never see a thing published? Would I be content toiling without recognition? Would I paint if nothing sold or showed? (Secretly, we hope this means we’re unappreciated in our own time. After all, Kafka! Dickenson!)

There’s an aloneness to art. We type, paint, sculpt, compose in isolation. We create to realize our theologies, philosophies, hurts, joys, doubts, faiths. We create to understand and work out our lives. And because we worship what we perceive to be the fount of truth and beauty (a God or gods, self, nature, universal energy, materials), we create to worship.

But while worship begins as a personal endeavor, it involves other people around us. My writing joins the chorus of voices, the cloud of witnesses, caught up in the melodies and harmonies and rhythms of the ages. It doesn’t matter if we’re writing story, sculpting marble, building a business, fixing the plumbing, or cleaning house. Our daily tasks as humans flow out of our worship, and our worship flows into the homes and lives of those around us.

Contra some Romantic notion of the artist alone and above the world (misunderstood by the world), art involves community. What has gone before — including the art, philosophies, and events billowing around the artist — influences the work, and the work (hopefully) resonates with everything around it. Art — and any act of worship — is communal. As we worship together, we build community rather than isolate individuals. Art is communion.

In a beautiful children’s book called A Winter Concert by Yuko Takao, a mouse goes to a piano concert. The music swirls around the audience in bright colors and shapes. As the audience members return to their homes, the music travels with them, painting the trees, their homes, their dreams. They send it out in letters to others. They record it in their diaries. The music doesn’t end with the concert but becomes part of them and part of what they do. As the composer and the performer share their art, others lay claim to it, inhale it, exhale it into their worlds in different forms. Art is a gift, both to us and from us. We find expression in it, but gifts find full expression in community.

Rather than creating in order to find or express our identities, we offer art freely to those around us. In the making and offering of art, we sacrifice our need for applause and affirmation, for repins and retweets, and witness to our experience of the world and of truth — beauty and corruption, groaning and rejoicing, pain and triumph.

This frees us to make and offer art in small communities. Like rural storytellers and musicians gathered on the porch after dinner, watermelon juice still sticky on their shirts, we testify to the magnificence, dignity, humor, sorrow, and redemption of the world around us as we finger-paint on construction paper with our children, write letters to our grandparents, pen plays for our community theaters, compose music for our churches, perform concerts for our friends.

Would I anguish over words if none would be read by others? No. That is not enough for me.

* * *

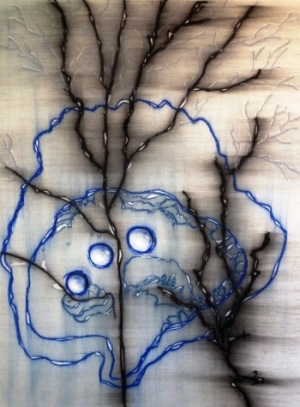

"Three Pearls" by Brenda Gribbin. Used with permission.Brenda brought over her piece along with a bag of her favorite tea and a packet of honey beads. Blue and black lines on a charcoal-rubbed background. Erased white spaces breaking through. An oyster superimposed across the trunk and branches of a tree. Three pearls incandescent in the center. I heard the rumblings of the ocean in it, the wind across the land. I saw nature breaking down and the gleam of hope.

"Three Pearls" by Brenda Gribbin. Used with permission.Brenda brought over her piece along with a bag of her favorite tea and a packet of honey beads. Blue and black lines on a charcoal-rubbed background. Erased white spaces breaking through. An oyster superimposed across the trunk and branches of a tree. Three pearls incandescent in the center. I heard the rumblings of the ocean in it, the wind across the land. I saw nature breaking down and the gleam of hope.

I had e-mailed her a short story of mine. We didn’t set any rules, but we knew that our purpose was not illustrative. She would not paint an image of my short story, nor would I write the story of her painting. Rather, our pieces would work themselves into each other, and we would dialogue with each other through our art. We’d create something entirely new yet made up of so much of the old.

I stood her piece on the desk next to my computer. I’d never created from an image like this. Usually the characters grew in my imagination until I could no longer ignore them, until I had to tell their stories. This, though, to start with an oyster and a tree, with three pearls.

My first attempt was a poem — a poor one, admittedly — of a woman wandering through her house post-Sandy. The lines of seaweed, the ocean trespassing onto land and leaving its mark. From this rubbing, with contours intersecting, white spaces broke through, windows into a larger story. A woman who lost everything, a woman hurtful and hurting, hoping and loving. I wrote the first sentence: “The day my boss turned into a frog, Hurricane Sandy whipped across the peninsula as if exacting revenge on the sliver of land that dared to dip between the ocean and the bay.”

Other influences — fairy tales I’ve read to my children, the writings of Benedict Kiely, Aimee Bender, and Colum McCann, the rampage of Hurricane Sandy, the narrative of Genesis — drew their lines in my story. The gifts of other artists threaded into this work. Sometimes I don’t know where they ended and I began. It doesn’t matter.

I stretched myself, not only with my starting point but in my storytelling. Mystical realism and fairy tale mixed with reality — a nod to the supernatural superimposed on the natural. The exercise pressed discipline into my amorphous life of toddler and infant, sick kids, meal planning (or, more likely, the last-minute scrounge for dinner), laundry, dirty dishes, and bathroom scrubbing. I was no longer responsible only for myself in this art. I had committed myself to another.

After finishing the rough draft, I wanted to hold back, to do the work of revisions and re-envisions before sending it to Brenda, but this is a collaborative work. She had texted images of her work-in-progress. It only seemed fair to e-mail her a taste of my perspective on her piece. I was nervous — what if she didn’t like the story that was twisted up with her painting? I wanted her feedback before starting revisions. True, the work is my perspective on her painting, on themes, ideas, notions caught up in the colors, lines and spaces, but a dialogue goes back and forth. She replied, “Wow, I love it! I laughed out loud in several spots, mostly because of the way you integrated the image into your story.” My blood pressure returned to normal.

When she brought her finished piece to my house, I wanted to caress it, to run my fingers along the textures of the paint. She had painted it, but in some sense, it felt like it belonged to me too. I saw the hurt and confusion and hope and healing from my story emerge in her painting. She got what I saw, and she saw more in it. When she took it home, I wondered how any visual artist parts with her work.

After more work on the story, I hope to shop it around, but if it never finds a home in a journal, that’s okay. I shared the joy of creating and of the creation. Perhaps Brenda and I should come up with a name for our new club.

Heather A. Goodman lives outside of Dallas, Texas, with her husband, two kids, and a parcel of imaginary friends. She loves short stories, Boba tea, and Curious George. You can listen to some of her short stories at www.noisetrade.com/heatheragoodman.