For years when I worked on Capitol Hill one of my primary responsibilities, surprisingly, was to reach out to various artists and celebrities from around the country to engage them in a thoughtful dialogue about the relationship between culture and politics. As one might suspect, this rare job brought me into somewhat regular contact with people who were sometimes quite famous. However, I confess that in nearly every instance the magic of their celebrity was lost on me. I simply don’t have what I dub the “celebrity chip” in my brain — their fame just didn’t faze me.

I became pretty convinced that God, in His mercy, had given me a nature wholly immune from the flush and hype of celebrity when I chanced upon an article in a theological journal that made my heart go pitter-pat. I wanted to blow up various excerpts of the article to full-size and make a poster in my room. I would have tweeted (against my better judgment) about this obscure and wonderful writer, but this was before Twitter was a big deal. I Googled the writer. I read in one sitting everything she had ever written, in part because it wasn’t much. I stalked her university homepage to read a bio, learn her favorite color, garner some insight into how a mere mortal could be so articulate and insightful. I found her e-mail address and then froze — how could I write to her? What would she say? What if she wrote back? “EeeeH!!!” my heart screamed like the shrillest Justin Bieber fan. And then it dawned on me. I had my first non-celebrity crush.

Since then I have discovered that many people — possibly everyone — has at least one non-celebrity crush. Mine is an English professor and periodic writer named Agnes, my husband’s is a Nobel economist named Ned, my best friend has a few designer crushes named Jenna and Emily (my friend is much cooler than my husband and me, so her celebs have much cooler names).

The thing about non-celebrity crushes is not that the celebrated individuals are wholly unknown — in many cases they are quite well known, even “famous” in the narrow scope of their field. Rather, it is that they are not likely to be known except by those who appreciate their particular field, who therefore appreciate the unique profundity or breadth of their skill.

The remarkable thing about the non-celebrity crush, then, is what it says about the crush-er, so to speak. The unsuspecting object of your enthusiastic esteem serves as an indicator of something you yourselves aspire to do. Just as the celebrity culture feeds on those who long to attach their identity to an admired other, the object of your own great admiration tells you quite a bit about your own loves and longings. It tells you a little bit more about how you aspire to contribute to your world.

Eccentric Love

Over the years I have experienced a few other moments like when I first encountered Agnes, when my unadulterated nerdiness has shone forth and I have lost myself in a fit of enthusiasm about something no one else on the planet likely cares about, loves, or even acknowledges, but which possesses me with inexplicable joy. This happened to me just last week as I was telling a friend about serving Communion at church.

In our historic Anglican church, communion is an aesthetically beautiful, as well as sacred, event. There are silver chalices, crisp white linens, gold crosses, cassocks, surplices, and plenty of other liturgical words, gestures, and objects previously unknown to me growing up in a non-denominational setting. In addition to the evocative language and poetry of the prayer book, every time I serve the blood of Christ to a friend in our congregation, to a respected mentor, to my sister, my boss, or my husband, I feel as if my heart might explode with joy for the sheer privilege of it.

As I told a friend later, “I love it so much I honestly don’t understand how other people are not clamoring over one another to sign up and do it themselves!” It was not an expression of judgment by any means, but a genuine mystery to me. How could others fail to be excited — exuberant, even — at the prospect of helping to nourish a human soul with such sacred food and drink? My dear friend, who I’m sure regretted asking about it, helped me realize what was patently obvious to her: Other people are not as gaga about liturgical order as I am.

Fair enough.

Love Shares

I air all of this nerdy laundry to make the point that only recently occurred to me — God feels the same enthusiastic bliss, the same exuberance, the same eagerness that compels me to share an astounding sentence by Marilynne Robinson, a poem by Kathleen Norris, a silver chalice, and so forth — only He feels this sheer delight about everything. Every single thing. I recognize this is not breaking news, but it is a funny thing that we can know something and yet not know it at the same time.

For as long as I can remember I have known that God created everything and declared that it was good. I know this. But for some reason it changes my perspective — it helps me — when I think of God being downright giddy about it. Even more, that He is giddy about the very things that make me giddy — infinitely more so, actually.

These deep and peculiar loves, these non-celebrity crushes of mine and my obsession with the bittersweet taste of sacrifice and redemption on my tongue, do not surprise Him at all; in fact, He is probably just as thrilled to see that I am finally starting to get what He’s been getting at all along. Hence why He shared it to begin with.

In my family I am one of four girls and our dad is a guy who loves to cook. We often joke that recipes are his “love language.” He is not overly affectionate, he is not particularly one for demonstrative gestures or quality time, but when he sends you a recipe you know it is his way of saying, “You should try this panna cotta because a) It’s awesome and b) I think you might enjoy it as much as I do.” In sum, it is my dad’s unique but effective way of saying, “Love ya.”

In countless ways every day I do this same thing. I love a recipe so I share it. I read a book that I love, so what do I do? Pass it on, of course. I hear a talk that I like, so I e-mail the link. I see shoes that are cool, so I text a photo to see if my sister wants the same pair (in a different color so we can share). Ironically, Twitter and Facebook and the entire morass of sites, links, and videos that comprise our modern social networks are based on the premise that people enjoy sharing what they love. Of course they do. Why do we suppose that God doesn’t?

In fact, God’s great and generous call to each of us is to take up the tiny, fun, curious things which animate our very being such that we can share in His delight and thus share in His creative and redemptive work. I have heard it said that these gifts are not my own. Indeed. And it is important that I be a responsible steward of them. But these alone are paltry truths. The greater, more exhilarating truth is that my skills and talents and interests, including even my quirkiest passions and most random affections, are those things God himself loves with such fervor that He is compelled to give them away. And, like any giver, His joy is made more complete when the recipient shares a sincere love of the gift, a richer relationship now made possible on familiar terms because of a common love.

A Way of Grace

Over the years, as I have allowed myself to embrace the mildly embarrassing truth that I possess a disproportionate, pathological love for eccentric things like etymologies and random English professors, as well as more widely appreciated things like spontaneous dinner parties and handcrafted pale ales, I have discovered that the people who are most dear to me — at least those who are remotely honest and reasonably self-aware — share just as many odd and lovely quirks. My best friend is obsessed with fonts and has a shockingly broad vocabulary for the possible range of colors (ochre, anyone?) that exist in the world. My younger sister bought an anatomy coloring book last week simply because the human vascular, circulatory, and nervous systems amaze her. My husband reads innovation theory in his spare time and adores the NBA. In getting to know myself and others in this way, I have also discovered that these peculiarities provide an accessible and winsome way to broaden my understanding of God, of love, and of grace.

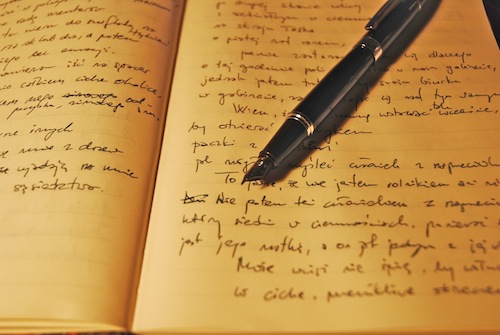

A friend of mine once said of Flannery O’Connor, “Writing is the way God gave her to experience His grace.” Since she first uttered this nonchalant, world-altering observation, I have not been able to get it out of my head. Writing itself is grace. What does that mean exactly? Is that true? Can it be? Surely scripture is a means of grace, prayer is a means of grace, the ministry of the Holy Spirit, wise counsel, teaching, devotional books — all of this feels familiar and plenty gracious. Yet when I think of poor, weary, peacock-loving Flannery sitting out on her roasting-hot, ramshackle porch offering up sentence after sentence of worship with her pad and pencil, I, a stalwart non-weeper, could cry out of sheer delight.

Of course it is true that writing was her grace. Why else would God set such love inside her? Inside us? Why else would I feel like in my moments of greatest love what I long for most deeply is to take out a part of my heart and set a little piece inside someone else so they can see and feel and taste and touch the wonder that I myself am seeing, feeling, tasting, and touching with such awe. And yet that is precisely what God has already done. He has taken His own deep loves and set them inside us — literally — so we can see as He sees and love as He loves, albeit imperfectly.

This kind of grace changes they way I live. So much of the way I think about my gifts, my skills, my deep loves, is out of a desire to steward them responsibly, to live generously, to serve, act, create, care for, and so on. These are all good and right, of course, and there is certainly much grace to be given and shared as each of us takes up our unique call to serve God creatively and redemptively in the world. Still, it is a different but important thing to acknowledge that those very gifts and interests from which I draw to give to others are, first and foremost, a means of grace to me. Like all grace, it is freely given, unmeasured, and from such bounty that we delight in sharing it.

I will say it again, “Writing is the way God gave her to experience His grace.” For young oddball Flannery this was surely true. For my friend Laurel, a fine artist, it might read, “Drawing is the way God gave her to experience His grace.” For my friend Susan it is textures. For my dad perhaps flavor or food. For all of us, it is something deeply familiar, yet perhaps a bit unexpected as we look on it with fresh eyes. And as we do so — in every instance of crush and admiration, of enthusiastic eagerness, of hidden or random bliss — we must be mindful that God has shared His deepest loves with us, and they are all grace.

Kate Harris is Executive Director of The Washington Institute for Faith, Vocation and Culture. She is a wife to a very good man and a mother to their three young children. She resides outside of Washington, D.C., in Falls Church, Virginia.