Writing to Remember

“The diarist has one essential goal: to freeze time. With each entry, he or she says that on this day, a day that will never again occur in the history of the world, I lived . . . This day will never come again, but here, in this diary, I will have it forever.”

—Pete Hamill’s introduction to A Diary of the Century by Edward Robb Ellis

I’ve been possessed by the archiving bug for most of my life. I’m terrible at throwing away anything that represents a piece of personal or family history. Mementos from my children and grandchildren, old negatives from the days before digital photos, desk calendars with a year of life scheduled in the pages, cards and letters — basically anything that has significance for me or my family story must be kept. That inclination, along with the urge to write, led me to the pages of diaries and journals.

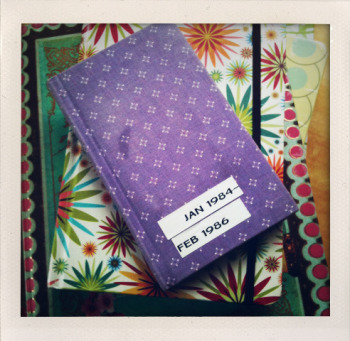

I started my first diary in the early 1960s soon after I learned to read and write. It had a pink, plastic cover with a lock and key. In high school and college, I wrote sporadically in spiral bound notebooks. In 1984 at the age of twenty-eight, I began to write steadily.

My mother passed away that year. After returning home from her funeral, I needed to process the experience and emotions of her death. With the help of a hospice nurse, my sister and I cared for her at home through her final days and nights. It was the most intense, frightening, yet intimate and loving experience I’d ever known. I came back to my own home, aching and devastated, with two small children who needed me. Pen and paper, the act of journaling, gave me unexpected comfort. Late one night I sat at the dining room table and hand-wrote a five-page narrative on typing paper of all I had just passed through. The next day I went to a bookstore and bought my first small, cloth-covered journal. In the days and months to follow, whenever I could find the words, I wrote down my grief.

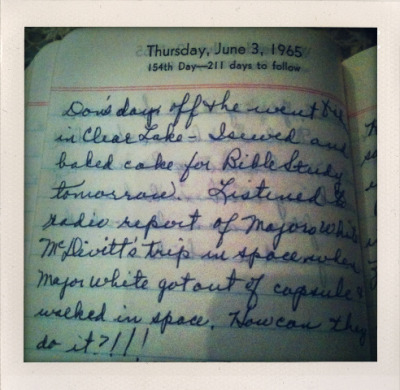

Andi's grandmother's diaryAlong with giving voice to my sorrow, I also began keeping a record of our days. With the guidance of my grandmother’s diaries, which my sisters and I inherited when she died in 1976, I kept a simple account of my work and the life of our family. I wrote down the ordinary details — meals I cooked, my husband’s musical projects, the work of our self-employment, books I read, illnesses in our household, the children’s activities, housework, time spent with friends, and my thoughts as a woman of new faith responding to the Bible for the first time. Everything mattered and no detail was too small. When the days were written down, they were noticed and remembered. Instead of fading with the passage of time, they were preserved. They had meaning. As the years went by and my documenting continued, I came to need the regularity of journaling and to value the history and perspective accumulating on the pages. Without realizing what was happening, writing became a part of me.

The act of writing in a journal provides a lovely pause of quiet in a busy life. I love a morning that begins with an open journal and a cup of coffee. Even in the crowded space of an airplane or coffee shop, a person engaged in putting words on paper can disappear behind an invisible shield of privacy. Many who write in diaries see it as a practice essential to their well-being. Once writing gets in your blood, the interior life feels messy and overloaded without it.

Writing helps us engage with our own life, but also with the larger world around us. With a journal at hand, we have a notebook in which to be a student of life. We can pluck ideas and phrases from a wise teaching, respond to a story in the news, write the highlights of an interesting conversation, or simply notice the grace of a beautiful meal and the company of others.

People who keep journals use them in their own unique ways. Two of my friends, a young engaged couple, kept journals and traded them back and forth when they were dating, but living in different cities. They chronicled their days, wrote love letters, and made favorite’s lists as a way of knowing each other more intimately from a distance. My husband uses his journals mainly for thinking through ideas, writing prayers, taking notes, and studying. He only rarely writes about personal experience in the way I do, and yet his stacks of journals are an archive of their own kind. In fact, the very first notes on his vision for Art House America are scrawled somewhere in a journal from 1990.

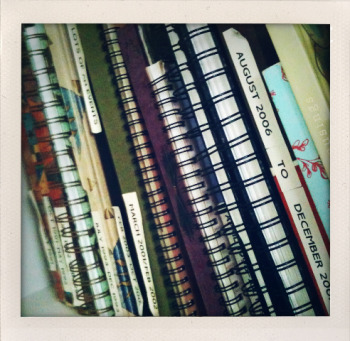

Andi's diariesI seldom write in my journal every day, usually only once a week. But I when I do, I always look back and write as much as I can remember about what took place between entries. The practice of writing things down, more than anything else, has given me the ability to see and understand my callings. In particular, the journals have given me insight into my work of hospitality, something that shapes my life in a way that’s unlike anyone else I know.

In the early days of Art House America, we hosted large groups of people every week for Bible studies, classes, and other events that connected Biblical teaching to all of life, with an emphasis on the arts and artful living. After the first six years we moved the steady, weekly commitments off-site to give our family a much-needed break. As time went by, I learned that our work of hospitality was far from over. Year after year our house continued to fill with people who came for a night or a week, for meals and conversation, for mentoring and counsel, and for special events. In looking back through my chronicles of our everyday living, I was able to see the story God was telling in our life with increasing clarity. Though there was often a connection between our guests and my husband’s work in the music business and later to my own work as a writer, and I could trace the reason many had come, there was no other way of explaining the volume and consistency apart from the words “calling” and “Art House.” My scattered journal entries made sense of all the parts of my work and named the central themes, hospitality being one of them. I would never have understood things as clearly without the narratives carried in my journals.

As journals stack up on the shelf, they become like history books. They hold our stories in the context of the times in which we live. Recently I’ve been rereading my grandmother’s diaries, looking for clues to my childhood. Since my grandmother kept a simple, daily record of her life and times, and reported family news with no embellishment, the accounts she kept are factual and trustworthy. Though I would love to know more of her thoughts and feelings, I’m grateful for her writing, the family history it contains, and the window of insight into a bygone era. Through daily reports of her work, community service, friendships, travels, habits, and family relationships, the small-town world of the 1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s is brought to light in a personal way. Her diaries are a gift beyond measure.

Last summer Chuck and I were privileged to go on a wonderfully unusual retreat in the hinterlands of British Columbia. Within an hour of arriving, our host led us in jumping off a cliff into the gorgeous waters of the Princess Louisa Inlet! It was a stellar beginning to our few days of adventure, delicious food, new friendships, and deep conversations. Every time we gathered for teaching and discussion, it struck me that most of the people at this small retreat for leaders in business, non-profits, music, and the literary and culinary arts, carried a journal and took careful notes. In the early mornings and late afternoons, many of them could be found on a rocking chair overlooking the water, soaking in the stunning scenery, reflecting in their journals. Every one of my new friends lives the fast-paced, fully-scheduled life of someone with large and complex responsibilities. Most of their communicating is done through e-mails, text-messages, blogs, and various forms of social media. Yet nothing could take the place of an empty book and pen. The physicality and portability of a journal tucked into a purse, brief case, or backpack has a steady value that hasn’t been lost in the digital age.

In my own life and the lives of others I know, journals provide a deep well to draw from when working on new creations. For authors and songwriters, artists of various disciplines, entrepreneurs, public speakers, and many other kinds of creators, the ideas jotted down, notes from books and films, responses to current events, and stories from everyday life can be a wonderful resource. Many times the work has already been done and the journals need only be mined for an illustration, a menu, a song title, or a wealth of thinking on a particular subject.

Andi's diariesThough all kinds of people keep journals, not just professional writers, by virtue of exercising the muscle you do become a better writer, someone practiced at bringing words and sentences from the mind and heart to the page. A love of writing is also a vocational clue and usually goes hand-in-hand with a love of reading. If you are someone who can’t not write, who enjoys writing so much that even letters and e-mails bring pleasure, pay attention. It could be that writing is something to pursue with all seriousness, trusting that God made you that way for a reason.

Anais Nïn wrote, “We write to taste life twice, in the moment, and in retrospection.” This being true, I record things honestly. Anything less would not be helpful. Both joy and hardship make their way into my writing, and the presence of each gives perspective. When life seems frozen in the shape of adversity, I look back to remember God’s sovereign care and see His grace in our lives more clearly. The journals give a witness to all the times we’ve been strengthened, provided for, or enabled to do something that seemed beyond us. I read in our stories a gradual change of heart or circumstance. I see great joys and times of celebrating, along with the sweet savor of ordinary days. The view broadens out and I’m able to say, “Because of the Lord’s great love we are not consumed, for His compassions never fail. They are new every morning; great is Your faithfulness.” (Lamentations 3:22-23)