"I want to know everything, everything," screeched Harriet suddenly, lying back and bouncing up and down on the bed. "Everything in the world, everything, everything. I will be a spy and know everything.

—Louise Fitzhugh, Harriet the Spy

When I was a child I remember having to do a lot of waiting. Standing in the grocery line, buckled in the car, slumped on uncomfortable chairs in waiting rooms. To make the time pass, I would “people watch” and wonder, Where is that person going? Where did they come from? Why do they look so angry? So happy? As I waited I would observe, really look at people. Their mannerisms fascinated me — their facial expressions, their shoes, their haircut. I would listen to them, their heavy sighs, their wheezing, the things they would mutter to themselves, and how they spoke to others. Sometimes they would see me watching them and look back with softness in their eyes and smile or wink. Other times they looked at me with a deep sadness. Occasionally, they would come over to me and tell me about their dog or their granddaughter.

However, most of the time these people never even noticed me. I was a perpetually curious and, at times, intrusive child — just ask my brother. One year when he was a teenager, I kept a notebook and wrote down every thing that I overheard him or his friends say, especially the juicy stuff . . . like curse words. You could say that Harriet the Spy was my heroine at the time. I suppose observing and wondering has always been something I’ve done.

Photograph by Anna TeschBut when I really think back, it’s also been a part of how I was raised. In traffic, when my mother would be cut off by a man in a speeding BMW, instead of shouting obscenities, she would gasp, then say, “Oh, that poor man! I think he must be on his way to the hospital. I bet he just received a phone call at work that his wife is in labor. Her neighbor had to drive her. She was so scared of having that baby by herself that she made him promise he’d make it in time. I hope he gets there quickly and safely.” And just like that she would turn a curse into a blessing, like a kind of magic.

Photograph by Anna TeschBut when I really think back, it’s also been a part of how I was raised. In traffic, when my mother would be cut off by a man in a speeding BMW, instead of shouting obscenities, she would gasp, then say, “Oh, that poor man! I think he must be on his way to the hospital. I bet he just received a phone call at work that his wife is in labor. Her neighbor had to drive her. She was so scared of having that baby by herself that she made him promise he’d make it in time. I hope he gets there quickly and safely.” And just like that she would turn a curse into a blessing, like a kind of magic.

As a child I thought she was magical. An avid reader, a teacher, and a writer, my mother was always full of stories. They flowed out of her as naturally as breath. Students loved her for it. They would run up to me on the playground saying, “Anna your mom is so funny!” “She told us about the time you ran away in your pink pajamas!” “Did that slug thing really happen?” At first I felt like some kind of elementary school celebrity. But after a few years of this, I began to grow tired of it. Sometimes kids would laugh like I was the butt of a joke. Occasionally a story was told that painted me in a less than flattering, albeit probably accurate, light. When the same story would come up on the playground, instead of feeling flattered or thinking my mother was magical, I just rolled my eyes and walked away. As I got older I began to even question the validity of some of her childhood stories as they gradually morphed a bit with each telling. New, more dramatic details were added to the last version. The stories seemed to grow as my view of her began to shrink. I had become a skeptical know-it-all. I had turned thirteen. While she began to tiptoe around my snotty and sometimes cutting remarks, she still had her other audiences. Her wide-eyed fourth and fifth graders hung on every word she said. The friends I brought home begged her to retell their favorite stories. She would look at me (and the look of disgust on my face), shrug her shoulders, and smile as she fed them homemade cookies and elaborate tales.

Stories are verbal acts of hospitality.

—Eugene Peterson, Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places

It was only when I became a mother that I realized how precious this storytelling gift was. I was a young, exhausted, and at times depressed mom of three under the age of six. Mom had retired from her many years of teaching and was determined to be the best damned Grammy and mother she could be. And she was. She would come over to the house with food and puzzles and sit and let me vent, and then promptly send me to shower and nap. I would always wake to the smell of something baking and the sound of her singing a song or telling the kids one of her stories. Even at their young ages, they sat quietly, eyes affixed on their Grammy as if she was an apparition sent to them by God Himself.

They weren’t too far off in their thinking. Though I treasured her gift during that time and credit her for my survival of those trying, mothering years, I began to grow jealous. I wanted my kids to look at me that way. I wanted to be the one to tell the stories. But at the time, I didn’t have it in me. Graciously she walked beside us through some of the biggest trials of our lives — a mysterious autoimmune disease, financial struggles, the painful loss of friends, and disillusionment with our church. All the while, she listened and fed us with her delicious food and words. She encouraged me to continue putting one foot in front of the other, to turn to God with my questions, to remember who I was, and to make the time to sit down and to give thanks for the good gifts I’d been given. Slowly, I went from surviving life to celebrating it again. In a way, her stories helped heal me.

The consolation of fairy-stories, the joy of the happy ending: or more correctly of the good catastrophe, the sudden joyous "turn" (for there is no true end to any fairy-tale); this joy, which is one of the things that fairy-stories can produce supremely well, is not essentially “escapist” or “fugitive.” In its fairy-tale—or otherworld—setting, it is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur. It does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.

―J.R.R. Tolkien, “On Fairy-Stories”

And then one day her stories stopped. It began with the flu and quickly turned into trips in and out of the hospital. My mother’s health rapidly declined and no one could figure out what was wrong. While my father and I navigated the health care system, researching her symptoms and taking her to multiple specialists, my mother drifted into another world. Heavily medicated, she could only stay awake minutes at a time, all the while in horrible pain. It’s a deeply disturbing experience to watch someone you love suffer and slip away. On the good days, I called my dad and got the daily report, I prayed the Examen, I went for long walks, and hoped for the best. On the bad days, I would hold it together at work and for my kids only to completely come apart sobbing on the floor of the shower. As January turned into February I began to descend into a darkness that mirrored my mother’s winter season.

One of my favorite stories is a children’s book called Frederick by Leo Lionni. It’s about a community of mice preparing for a winter. They are all busy gathering food and supplies, but Frederick never seems to be helping. He gazes far off into the meadow and closes his eyes for long periods of time. The other mice complain, thinking him lazy. Winter comes and they all hunker down amidst their supplies in the stone wall. The season ends up being colder and longer than they had planned for. Their food, conversations, and hope run low. And that’s just when Frederick rises to the occasion. He tells the mice to close their eyes and begins to tell them stories of the sun’s warmth, describes the colors of the red poppies and the golden wheat then recites a poem about the seasons. The mice begin to feel warm, and they can imagine the colors from spring and find joy again amidst a bleak winter.

One cold and sleepless night I was suddenly overtaken by a thought that gave me such a panic that I immediately got up, wrapped myself in a quilt, and went to the kitchen to make myself a cup of tea. What if this was it? What if my mother never came back to us? What if all the stories I had heard my entire life went with her? I remembered back to the loss of my mother’s father, my Papa. One of the waves that hit me and nearly knocked me over in the mourning process was the realization that there were many questions I never got to ask him. There were parts of his life, his childhood, tales of his trips at sea, of his marriage to my Nana, of the loss of his only son that would never be told. The thought that some stories die with their keeper was an overwhelming and crushing blow. I felt determined to not let that happen in my family.

And that’s when the Harriet the Spy spirit came back to me. Where was he born again? When did he move to Bainbridge Island? One question led to another until I had ventured down the slippery slope that is genealogical research. Like a detective, I spent hours online pouring over old documents in beautiful, flowery script about one relative or another; first filling in the basics (place of birth, year of marriage, occupation, number of children) and then researching context (what was going on in history during this time and what kind of struggles must they have faced).

Suddenly I sensed that a great cloud of witnesses surrounded me. The more answers I got, the more peace I felt. The journey of discovering the stories of those who came before me made me feel like a part of a bigger story. Ancestry research mostly satisfied a deep longing within me to belong to a greater narrative. It infused my life with new meaning. Instead of it being a mere distraction, it served to draw my attention beyond my current dark night of the soul. The more I read about my relatives and the hardships they lived through, the more my dim flame of hope grew stronger in my present circumstance. And that’s exactly what stories do for us, don’t they? They sustain us.

In the spring, along with the fields of vibrant tulips in the Skagit Valley, my mother resurrected. She slowly came back to us. First, in presence — she was able to stay awake for longer periods. Then she was able to walk again and move about with a marked decrease in pain. And lastly, in spirit — the sparkle in her eye, the mischievous turn at the corner of her mouth, and the stories! The stories came again. And this time, fresh from the harsh realization of just how close I came to losing my mother, I simply listened. And I’m still listening.

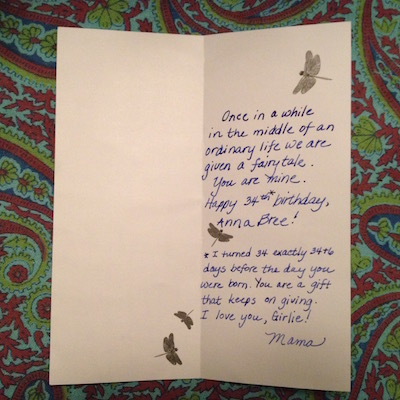

This past September I turned thirty-four and the highlight of my day was going out to brunch with my mama. We sat together in the corner of my favorite restaurant, shared a dish of eggs Benedict, and drank cup after cup of coffee. She told me about her latest adventure visiting her sister in Forks and about a hike they went on together. She had pushed herself to her physical limit, even asking a stranger for help, climbing a ladder because she was determined to see the gorgeous coastal seascape. She was glowing. I sat in awe. She laughed about the Twilighters at the local diner and told me about every meal they ate, in great detail. And I ate it up. Then she set a card covered in dragonflies in front of me. When I opened it, I burst into tears. Right there during the brunch rush I hugged her and wept. Being there with her was the best gift I received this year. Every day with her and her stories is a gift.

Photograph by Anna Tesch

Photograph by Anna Tesch

Anna Tesch has been married for 15 years, is the mother of three blue-eyed beings, a daughter to supportive parents, a sister, an aunt, and a friend. She works for her local school district and cooking school, and sings and cuddles babies at her church.

Some of her favorite activities include cooking, singing along to her vinyl copy of Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Cole Porter Songbook, listening to poetry, writing, having conversations that spark great thoughts, genealogy, visiting museums and bookstores, people-watching, taking long walks by the water, and bringing books to bed. You can interact with Anna on Twitter.