The transforming moment in Christian conversion comes when we realize that even God has left us. We then discover it was not God, but our image of God, that abandoned us. This frees us to discover more of the mystery of God than we knew.

—Craig Barnes, When God Interrupts

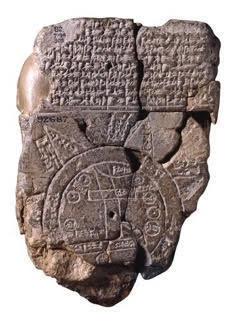

One of the oldest maps in existence shows only a fragment of the world and yet reflects the universe. Carved on a small clay tablet in 500 B.C. Babylonia, the map depicts the earth as a flat circle surrounded by a ring of ocean. It includes what was important to its makers: the city of Babylon as the center of the world, a mountain range, the wide Euphrates River, and the neighboring lands of Assyria and Chaldea. Triangles represent islands beyond the ocean where creatures common to Babylonian legends lived. Much of the space outside the ocean’s ring is blank.

One of the oldest maps in existence shows only a fragment of the world and yet reflects the universe. Carved on a small clay tablet in 500 B.C. Babylonia, the map depicts the earth as a flat circle surrounded by a ring of ocean. It includes what was important to its makers: the city of Babylon as the center of the world, a mountain range, the wide Euphrates River, and the neighboring lands of Assyria and Chaldea. Triangles represent islands beyond the ocean where creatures common to Babylonian legends lived. Much of the space outside the ocean’s ring is blank.

Today, of course, technology has widened our understanding of the globe. The ocean is no longer distant. We know the heights of thousands of mountains and the names of thousands of enemies. We have different ideas about what country is the center of the world.

Most significantly, our culture leaves few places on a map blank, unexplored, unrealized. Whether it’s a movie title, a theological truth, or the best burrito in town, the answer is out there and must be known.

But what do all these answers do to the soul? Where do we carve out the mystery of not knowing but believing? We forget that our spiritual journey depends upon truths we don’t fully understand, places we have not yet traveled.

My husband and I have a reproduction of a 1775 map of the Caribbean hanging in our bedroom, along with a map of the world from 1570. An 1883 map of the four-cornered states hangs by our closet, and every day we walk on the same Colorado ground it represents.

Hands drew and colored every inch of these maps, copy after copy, because someone believed place was worth recording. They survived invasion and violence, water and blood. They reflect the best scientific and cultural knowledge of the time.

And each one of them is wrong. Each one of them includes false assumptions, outdated ideas, and misconceptions based on the mapmaker’s personal biases.

Ancient maps remind me that I too chart my days with assumptions that may or may not be true. I label lands as if I have set foot there, when in fact I have only heard stories of stories. They remind me that I can stand rooted in earth, warm and rich, and still have much left to discover.

* * *

My grandfather was a man who knew less and less and believed more and more. I remember listening to him talk about the Second World War when I was a child. He often quoted a verse from Nahum, the King James language warm in his voice: “The Lord is good, a strong hold in the day of trouble; and he knoweth them that trust in him.”1 He carried those words in his spirit as truly as he’d carried a bullet-proof Bible in his breast pocket across France and Italy, not knowing if he would return home to his wife and son. The Lord is good.

My grandfather lived his final years in a nursing home, he and my grandmother sleeping in separate beds for the first time since the war. Some days, a nurse wheeled him down the hall to a Bible study. He would sit and listen for a time and then start praying out loud, in the middle of a lesson, his voice booming in the small room. The group leader would stop teaching and the residents would bow their heads, and my grandfather would pray and then fall asleep.

The last time I visited my grandparents, I sat holding my grandfather’s hand, his fingers flat and smooth as tissue paper. God was one of the only things he still had by that day. He’d seen boxcars in Dachau. He’d watched newsreels of children dying in Vietnam. He’d witnessed presidents and economies and churches fail. He’d lost every friend he had — most to death, some to memory. He still played the harmonica, as he had as a soldier, and he still loved to eat. But what he held most tightly were the words of Scripture, the verses that wove through his thoughts from childhood to Normandy. The Lord is good.

Earlier in his life, my grandpa was known for his strong opinions. He had much to say about the American church, the speed limit going up to 55 miles per hour (“Next thing you know, it will be 65!”), and politics. He probably would have shared many posts on Facebook that I would have disagreed with. But the older he got, the less he spoke about what he knew and the more he spoke about what God knew.

This comforts me when I feel lost on my own spiritual travels. Facebook fury and Yelp reviews and the constant call to have an opinion leave me fragmented, disoriented. I long for the fertile ground of humility, the place of “inner silence [that] frees you from the burden of thinking that your judgment is needed or important.”2

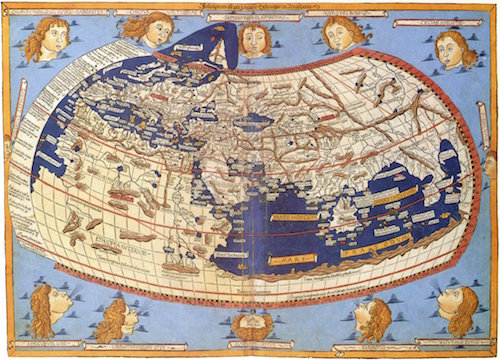

I look at the map of the world on our bedroom wall. Ancient cartographers were certain that a body of land enclosed the Indian Ocean, joining Africa in the west and Asia in the east. Maps included this large southern continent for hundreds of years, even after Magellan and other explorers found no evidence of such a land. Mapmakers of the 1500s labeled this imagined continent “The Southern Land Not Yet Known.”

Just like this ancient map, my faith has wide-open places, unlabeled, unknown. My understanding of myself is also limited, as much as I try to figure out who I am. And though I attempt to sketch the coastline of my soul, God knows every intricacy of that country — the colors, the animals, how the trees look at dawn. I rest in knowing that truth is not dependent on my understanding of it.

Questions, debates, and theological wonderings are important. They are the ancient maps building on each other that help us find out where we are going so we can discover truth. But they are not truth themselves. God is too good to leave such things up to us.

And so while many of us use the Bible to speak of how much we know, the Bible itself reminds us how little we know. We learn that God’s ways are higher than ours and his thoughts so far from ours that we cannot comprehend them. The peace of God is beyond all knowledge. Faith is a mystery.3

This is what I know today: The Lord is good. Love one another.

God’s truth is the island that exists whether we put it on the map or not. The mountain that lifts spectacular in the clouds while we study the grass below.

Every week in church, I stand with my husband and daughters as the priest says: “Therefore, we proclaim the mystery of faith.” We respond: “Christ has died. Christ is risen. Christ will come again.” We proclaim the mystery. What a beautiful declaration of certainty in the unknown.

As so many faith-explorers before us have discovered, mystery is a remarkably safe place to be. Richard Rohr writes that when you are willing to lean into the paradox of faith, “The Holy Spirit frees you from taking sides and allows you to remain content in the partial darkness of every situation long enough to let it teach you, broaden you, and enrich you.”4

I want to be aware that God has much left to draw on the map of my faith. Whether I need to add something back that I have erased or pencil in a new land, I want to live exploring. I want to understand that I am always wrong about something.

“The Southern Land Not Yet Known,” the ancient cartographers wrote. Named though not yet seen. Sketched though not yet discovered. Unchanging while waiting to be found.

* * *

When my dad was a boy, he vacationed every year with his parents and his brother in Ocean City, New Jersey. There my dad played Skeeball, ran on the beach with my uncle, lapped up root beer–flavored water ices.

My sister and I knew these stories and heard the pleasure in my dad’s voice as he told them. Ocean City became for us the remembrance of a happy childhood even before we had lived it.

We visited my grandparents in Philadelphia every spring break and always went to Ocean City for a day. As we rode surrey bikes and braved the ocean with our toes, my grandparents received the day from a bench. The boardwalk offered such promise in its woody sounds that we nearly expected to find my dad as a ten-year-old look up from his water ice as we rumbled past.

The day we drove to Ocean City for the last time took the shape that only last times take. Both my grandparents were growing frail. It was on that day that we realized my grandpa’s vision was not just fading, not a tunnel closing in or a gauze sliding down, but he couldn’t see. This was the intimacy he and my grandma were keeping, the dimness he did not talk about. How could he describe the light that came only from the corner of one eye? How could he explain how long it takes to say goodbye to color?

We fell into silence looking at our menus for lunch, aware of my grandfather staring straight ahead. My grandparents began to laugh.

“It’s just that Herbie can’t see, so I read him the menu,” my grandma said. “But then he can’t hear, so he asks me what I said. But I can’t remember! It takes us a long time to order these days.” They started laughing again, the familiar laughter of long-loved years.

When it was time to go home, my dad went to get the car and the rest of us eased ourselves away from the water. As we waited on the boardwalk, I inspected my shell collection, dusting sand out of the crevices.

When I looked up, my grandpa had turned to the ocean and the seagulls. He wore his brown beret and leaned on his cane and I imagined blackness hiding all he once loved. Yet his eyes were not on the flurry of the beach but on the waters ahead, waters neither one of us could see.

He heard me come up behind him and he smiled. Without taking his eyes from the distant ocean, he whispered, as if hearing a secret he had to tell, “Isn’t it beautiful?”

Elisa Fryling Stanford is a writer and editor in Colorado Springs, Colorado. She and her husband, Eric, have two daughters.

1 Nahum 1:7, kjv.

2 Richard Rohr, Silent Compassion (Cincinnati, OH: Franciscan Media, 2014), 26.

3 Isaiah 55:9; Philippians 4:6-7; 1 Timothy 3:9.

4 Rohr, 11.