Interview Series: MAKING — A Conversation with Bruce Herman

It's a pleasure to feature Bruce Herman, a wholly admirable artist/educator in our second interview in a series on Making. As Daniel Nayeri quoted in Comment magazine, “Bruce is a great man and a great artist.” I couldn't agree more. Bruce is a maker full of skill, wit, and a watchful eye.

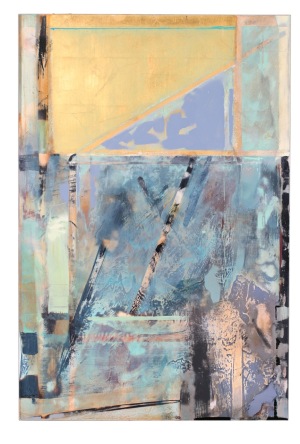

"Palimpsest" by Bruce Herman

Charlie Peacock: Where were you born?

Bruce Herman: Montclair, NJ.

CP: How does place inform your making today?

BH: It is pivotal. In a large body of paintings entitled Presence/Absence (thirty-five abstract land-based paintings that form an installation or ”world” around a central Adam figure) I tried to evoke the place where I live — Gloucester, Massachusetts — which is a glacial moraine and a cape (Cape Ann) as well as one of the oldest settlements in the United States. In this body of work I’ve tried to give a sense of geological time and the profound mystery I feel etched in the granite ledges and boulders here. There is also the ocean and its tides and the estuary at the end of our street, which begins the Great Marsh — a tidal marsh that stretches from here to Maine. The impermanence of tidal things over and against the immovable ancient rocks, this mystery of weather and tide, passing-ness and permanence. These are the things that have come to define my sense of place, and that has figured heavily into my work.

CP: What about people? Are there any particular people you point to as imaginative, creative influences, whether you knew them or not?

BH: Lyn Ott, a painter I worked for when I was eighteen. He was a mystic, a deeply sincere and inventive man who continued painting even after he began going blind. T.S. Eliot for his understanding, extending of living tradition, and for his astonishing poetry. Rembrandt for his glimpses of the soul and for his paint that becomes flesh and blood in a transcendent, almost magical way. Fra Angelico for his humble servant posture as an artist — putting the needs of his community ahead of his own preferences. My best friend and wife of nearly forty years, Meg. She has an almost scary “eye” — that is, she can detect instantly where my paintings have gone wrong, both on a technical and emotional level. I am not exaggerating when I say that she can walk out into a field of clover and within ten minutes comes back with a half dozen of those rare four-leafed clovers. After forty years I am still dumbstruck.

CP: That’s beautiful about your wife Meg, and a great testimony to the collaborative power of marriage. Thank you for that.

I see your work as being diverse and having many touchpoints to everyday life, yet I also know you as someone who doesn’t shy away from incorporating your spiritual beliefs and practices into your work as well. In fact, I’d commend you as someone who does this seamlessly. But there are many people who make religious things and who in particular, associate themselves in some way with historical religious characters — in your case, Jesus. Do you consider yourself to be a Christian? And if so, what exactly do you mean by that sort of profession?

"Spring" by Bruce HermanBH: Though I self-identify as a Christian culturally speaking and try to follow Jesus, I am quite torn about religion. I do feel it is important, humanly speaking. We need religion just like we need sleep or food or procreation. We need religious ritual. The question is always there, however: what does our ritual point toward, what does it “channel”? A lot of Christianity is really what I’d call Christianism — i.e., a man-made religion. But the truly important things in life all revolve around relationships, and that’s true for how we understand God as well. So I’d say for me being a Christian is a conflicted thing, but a deeply significant thing — and at the heart of my faith is not a set of beliefs but a lived relationship with Christ.

CP: Well said. So as you live with the conflict, in search of significance, what do you make? What do you bring into the world that wasn’t there until you created it?

BH: I’m a painter. I have been making paintings for forty years, so apparently I don’t have an “off” button. Every two to three years I seem to initiate a new body of work, like the Presence/Absence paintings. All of my distinct groups of paintings seem to be about the journey of the soul through time and place and the human/divine drama. The latest body of work just completed is a response to T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets. It’s a collaborative project with another painter, Makoto Fujimura; a composer, Christopher Theofanidis of Yale; and a theologian, Jeremy Begbie. We’ve almost completed all of our work, and the exhibition and concert tour begins this fall at Baylor University then travels to Duke University, then to Yale, and next April to Gordon College, where I taught for over 25 years. The tour then shifts to Japan and China. This project is possibly the most exciting thing I’ve ever done. But then every new project is the most exciting thing to me.

CP: I wish you well with the tour. Tell me about your favorite tools/materials you use in your making, and do you have a favorite workspace?

BH: I use all sorts of different paints and surfaces — oils, acrylics, encaustics, conté, charcoal, canvas, wood, etc. I make the work in layers — many layers — and then often abrade or sand or scrape through layers revealing the history of the making of the painting as part of the “subject matter” of the piece. I work in an art studio that I built on to our home. It is about 600 square feet of workspace with northern-lit skylights, a high ceiling, and a plain “industrial” workshop feel.

CP: As an exercise in self-understanding as a maker, can you give me five separate, individual words that describe your creative work?

BH: Risk. Insight–eyesight. Story. Texture. Color.

CP: Finally, when you dream of a better planet and culture what does it look like? And specifically, what is your hope for what you’re making and bringing into the world? How do you imagine it contributing what is good, just, right, or beautiful?

BH: I dream of the world as sacred space — as a living cathedral. Man-made cathedrals merely echo the natural world with its soaring sequoias, canyons, oceans, mountain peaks. This world was made by a Maker who loves and enters the creation to know it from the inside. This Maker is not aggressive or possessive as we humans understand Him, but is rather hidden, loving, generous to a fault. I dream of the Creator being honored in all things by all His creatures — not because this is forced, but because we choose to honor Him. I hope that my work honors the Maker. For years I used my art to call attention to myself and I am not proud of this. But I have learned my lesson and want nothing more at this point than that my paintings point toward that sacred space of honor for the only one true Artist, who gave himself away in his Creation. That’s what I want to do to make this world better — give myself away, following the Maker’s way.

F O U R Q U A R T E T S from bruce Herman on Vimeo.

Bruce Herman (American, b. 1953) completed both undergraduate and graduate fine arts degrees at Boston University School for the Arts. He studied under Philip Guston, James Weeks, David Aronson, Reed Kay, and Arthur Polonsky.

Herman lectures widely and has had work published in many books, journals, and popular magazines. His artwork has been exhibited in more than 20 solo and 100 group exhibitions in eleven major cities including Boston, New York, Chicago, Washington, DC, and Los Angeles.

His work has been shown internationally, including in England, Italy, Canada, and Israel. His art is featured in many public and private collections including the Vatican Museum of Modern Religious Art in Rome; The Cincinnati Museum of Fine Arts; DeCordova Museum in Lincoln, Massachusetts; and the Hammer Museum, Grunwald Print Collection, Los Angeles.

Herman currently holds the Lothlórien Distinguished Chair in Fine Arts at Gordon College, where he has taught for 29 years. He is also a board member of CIVA (Christians in the Visual Arts).